How money from sick people works, Part II: The 340B story

A january unlike any other

In case you didn’t notice from our last report on new year price changes, at the end of December 2023, many insulin vials and pens took significant (i.e., 75%+) list price decreases. Given much of the early 2024 attention on brand drug list price increases, it bears repeating that insulins in 2024 are largely a quarter of the price they were in 2023. This cratering of prices for a number of high-profile brand products in unison with others (e.g. respiratory inhalers) is largely unprecedented.

The significance cannot be overstated. Arguably, no products have more exemplified the drug pricing dysfunction of the United States than insulins over the last 30 (and arguably, 100) years. As we are often reminded, the original insulin patent was sold for a $1 (even if the patent in question was essentially a patent for ground-up animal pancreas; US Patent #1469994).

Yet, despite insulin’s meager origins and the proliferation of diabetes diagnoses – which today impacts more than 38 million people in just the U.S. alone – thanks to congressional investigations, media reporting, manufacturer disclosures, and loads of research, we know that the real story of insulin pricing has become healthcare’s sad version of “Where’s the beef?”

Here at 46brooklyn Research, we too have used insulin as the bloated punching bag that it deserves to be, because as list prices and net prices for insulin have diverged over the years, the full value of the growing drugmaker discounts were often not making their way to the end payer.

As such, we have focused on insulin as an example to demonstrate how drugmaker rebates are really just “money from sick people.” This is because drugmaker rebates are little more than money collected by government programs, pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), rebate aggregators, insurers, and/or plan sponsors – on prescription drugs taken by sick people – that are often used for purposes other than lowering the cost of the medicine for that sick patient, like say to lower premiums for all people covered by the plan.

As we showed in 2021 (and as was expertly highlighted by USA Today at the time), the rebate system imposes great financial harm on those burdened with insulin dependency and the other corresponding costs associated with diabetes management. To quote from our 2021 report:

“What our models show us is that patients are over-paying for vital prescription drugs. In the current “Money from Sick People” environment, a patient expends $1,906.72 annually per year on Lantus alone (absent any premiums they have to pay, and without consideration for diabetic supplies they’ll need to use Lantus properly). The health plan’s total net expenses are -$1.078.72. That is to say, the health plan made around a thousand dollars off the sick patient’s drugs. They did this by collecting and banking rebates during the first four months of the year, and then using those rebates – plus the rest of the rebates that they generate over the remainder of the year – to pay for the expenses to the pharmacy to acquire and dispense the drug (and it just so happens that they have some money left over at the end).”

Because of the severity of the insulin pricing problem, we always intended to revisit it to demonstrate other ways money from sick people works. So before drug pricing critics move onto the next shiny object and insulin fades into the rearview of our collective understanding of drug pricing dysfunction, as a result of these list price decreases (which also reduces the rebates they’ll produce), we invite you to join us in another look at how our system’s addiction to discounts distorts the marketplace and creates winners and losers among drug channel participants and end payers.

In today’s report, we take you into the abyss of the 340B program – a Sarlacc pit of drug pricing complexity that few dare to enter – to provide a new lens with which to understand how patients can be adversely impacted by a system built on special deals.

If you are already familiar with the 340B program’s mechanics, feel free to skip ahead to the Our Analysis section, but if you aren’t, we highly recommend reading the below section on The Origin of the 340B Program.

With that, we give you: Money From Sick People, Part II: The 340B Story.

The origin of the 340B program

Typically, when prescription drug rebates are discussed and debated, the common tug of war lives between drug manufacturers and PBMs. Because PBMs represent so many covered lives, drugmakers understandably want PBMs to cover the medicines that they produce. For medicines within competitive classes, PBMs can use their leverage to shake down manufacturers for big rebates in exchange for coverage and preferential treatment for those medicines. While this may lower the net prices of medicines relative to their list prices, it is often argued that the pressure for bigger rebates and other like-discounts disincentivizes manufacturers from lowering list prices, and in fact, could pressure them to do the opposite. This dynamic also arguably results in perverse incentives for PBMs, who stand to bring in more money off medicines with higher list prices (and higher rebates). Thus, you have controversies brewing at the federal level today where there appears to be tailwinds behind efforts to “delink” PBM compensation from the list prices of medicines.

While legacy PBMs are getting their deserved moment in the sun for their role in distorting this marketplace and arbitraging drugmaker discounts, in fairness, they aren’t the only ones with their hands in the drug pricing cookie jar.

As many have probably heard, under the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), Medicare starts getting their own penalties and rebates from drug manufacturers. While the way the IRA goes about harvesting those rebates in Medicare may differ, rebates and special deals for government programs in the U.S. is hardly new. For those who don’t know, thanks to the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990 (OBRA ‘90), Medicaid programs also get their own rebates from drug manufacturers through the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program (MDRP).

Figure 1

Source: U.S. Office of the Inspector General

When Congress enacted the MDRP, they decided not to directly negotiate/set drug prices (like much of the rest of the western world); rather, they decided to obtain retrospective discounts off manufacturer-set list prices. An Office of the Inspector General (OIG) report in 1990 makes it clear (in our view at least) that brand price negotiation was under consideration at the time, but ultimately other controls (i.e., rebates) were selected.

What OBRA ‘90 did in establishing the MDRP was to set a formula to determine the Medicaid rebate amounts.

The formula states that Medicaid was due a manufacturer rebate on the drug on the basis of: (1) A percentage of the drug’s price (not the typical wholesale acquisition cos [WAC] list price, but average manufacturer price [AMP]) OR Medicaid would get the best price negotiated; and (2) Medicaid would get additional rebates if the price of a drug rose faster than inflation. Note that the law required manufacturers to report both the AMP and the “best price” to the government for the purposes of calculating the Medicaid rebate.

So while the government was not necessarily going to be involved in negotiating prices, they’d get the benefit of negotiated prices from the competitive market (via the “best price” provision), as well as the benefits of a penalty (a disincentive) to not raise drug prices too much (at least not higher than the rate of other goods and services). Regardless of the details, in practice, the precedent was set that Medicaid programs would be required by law to get the “best price” in the market.

As a consequence of this formula, drug manufacturers pulled back on purchase discounts offered to select healthcare providers (they didn’t want to give Medicaid the best price they were giving to providers).

Obviously a local hospital has a far smaller footprint than a state Medicaid program; so are we really surprised manufacturers acted in this way under this new law? The pull-back on drugmaker discounts to healthcare providers as a result of the MDRP best price birthed calls for adjustments in Congress.

So in 1992, Congress passed the Public Health Service Act. Contained within this act is Section 340B, which established a program whereby select healthcare groups (what we call Covered Entities) could purchase drugs cheaper than market rates – rates equivalent to what Medicaid got in terms of rebates. The creation of the 340B program and its extension of government-mandated discounts to Covered Entities was a stealthy way for former Senator Ted Kennedy and the balanced budget congressional Republicans of the 1990s to offer a new entitlement program at no readily-discernable federal budget impact (at least on paper). By effectively stating, “providers, you can buy drugs at the same net prices we the government get for Medicaid,” they did not need to apportion any meaningful budgetary funding for the program, while at the same time, rectifying the problem in the minds of the impacted healthcare providers who got access to buy cheap drugs again.

To be clear, participants in the 340B program (i.e., Covered Entities and their affiliated partners) make money off the system the old fashion way – buying the drug cheap and selling it high. Because the 340B program is a discount on drug purchases, Congress effectively created a complex subsidy for 340B Covered Entities achieved through requirements imposed on drug manufacturers. Via the 340B program, Covered Entities are able to purchase drug inventory at a significant reduction in cost, beyond what they would otherwise negotiate in the typical commercial marketplace (i.e., “best price”). After securing low-cost inventory, which itself frees up the business’s carrying costs, Covered Entities rely upon the second source of their subsidy — privately insured individuals — to generate revenue on these discounted drug purchases. This funding (i.e., the profit between sale price and purchase price – loyal 46brooklyn readers might be thinking of the familiar term, “spread”) enables Covered Entities to deliver care to the uninsured or underinsured. As stated within an old Health Resources and Services Administration’s (HRSA) Hemophilia Treatment Center Manual, “If the covered entities were not able to access resources freed up by the drug discounts when they apply for grants and bill private health insurance, their programs would receive no assistance from the enactment of Section 340B and there would be no incentive for them to become covered entities.”

So for those who were previously unfamiliar with the mechanics of Medicaid rebates and the 340B program, hopefully this gives a better understanding of how these government entitlement programs impact the drug pricing landscape. With the goals of Medicaid and 340B essentially concentrated on the noble purpose to provide healthcare for those who otherwise would not be able to afford it, the rub becomes how the programs go about achieving those ends — which is to draw its financial lifeblood from the list prices of medicines and the spreads harvested from patients and plan sponsors instead of more traditional budgeting means. And regardless of the return on investment received from Medicaid and 340B, the prevailing wisdom is that somehow, the yielded rebate dollars occur with no costs to the system.

Sounds all pretty amazing, right? We can fund big programs like Medicaid and 340B by just hitting up the drug manufacturers for discounts off their prices, and that way, it doesn’t cost the rest of us anything. And now with Medicare getting their own rebates through the IRA, it begs a larger question: if we could just drive more discounts from drug manufacturers, what other sorts of cool stuff could we then get for free?

Of course, it doesn’t really work this way. In fact, it was clear pretty much from the beginning that there was a link between these government programs and the rest of the market. There is no secret drug money tree that keeps replenishing itself (outside of Woonsocket, that is). These discounts may not have a direct, easy-to-decipher cost on the front end, but somewhere, somehow, this money has an origin story.

And much like our Money from Sick People tale from 2021, the drug discounts that underpin the Medicaid and 340B programs don’t come without a cost either. The old saying goes, “there’s no such thing as a free lunch.” So when it comes to 340B, let’s see who is getting to feast and who is picking up the tab.

Our analysis

As with any good analysis, we need to start with some data and some assumptions. Fortunately for us, all of our data for this analysis of the flow of dollars within the 340B program is publicly sourced, so feel free to check our work, and thank those who make drug pricing data more available and accessible to the public.

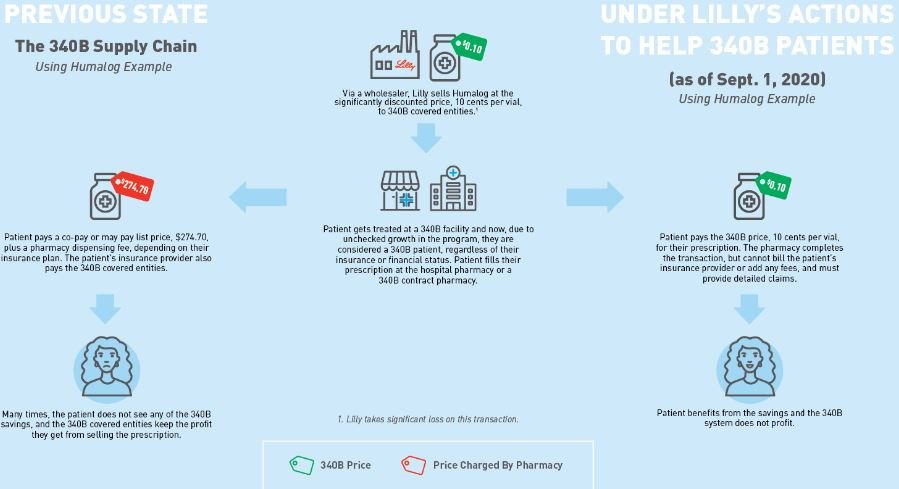

Our first assumption is to establish what the 340B price for insulin actually is. Fortunately for us, Eli Lilly told us the 340B price experience for their drug Humalog (as of Sept. 1, 2020). As can be seen below in Figure 2, Eli Lilly (who would know best) told us that the list price (i.e., wholesale acquisition cost, or WAC ) for insulin was $274.70 for a 10 mL vial. That same vial could be acquired through the 340B program for just $0.10 (an effective 100% discount).

Figure 2

Source: Eli Lilly & Co.

Now, this is the price of insulin as of September 2020 according to Lilly, but we believe it still holds valid through the end of 2023. There were no WAC list price changes for Humalog between September 2020 and 2023 (except of course for 76% decrease in WAC list price on 12/30/2023 – see our Brand Drug List Price Change Box Score). Because there were no list price changes, we think it’s reasonable to say this graphic is valid for the years of 2020 through 2023 (except for the 30th and 31st of December 2023). Nevertheless, we’ll endeavor to keep our timeline close to this date as the purpose of this report is more demonstrative than quantitative.

Our next assumption is to establish what the average deductible amount is in the U.S. We need this value, because it establishes how much money a patient will have to pay directly for their healthcare products and services – in our case, the drug Humalog – before they get the benefit of their insurance copayment. Thanks to the Kaiser Family Foundation 2020 Employer Health Benefits Survey, we sourced this at $1,644 annually for 2020 (aligned to the date of Eli Lilly graphic in Figure 2).

Next we need to know what Humalog costs – what it costs for the insulin package to the health system, and what a patient pays to get that package after they’ve met their deductible. Fortunately, this was recently looked into through our team’s consulting work at 3 Axis Advisors, where using our recently-released World Insulin Price Comparison Map, we can see that the typical package cost for a vial of Humalog vial is $262 in the U.S., with a typical patient pay obligation of $25.72. The cost of the vial of pens reported there is at least in line with our own visualizations at 46brooklyn, assuming Medicaid managed care organizations are reasonable proxies to the commercial market, and also in line with other previous disclosures on price.

Now, the astute reader will note that $262 relative to the WAC list price of $274.70 is roughly a $10 underpayment to pharmacy. For the sake of making all of this easier, we’re going to go with the $274.70 number for both the reimbursement and acquisition cost number (but there is almost certainly a lesson there about underwater reimbursement on brand name drugs to pharmacies). In choosing to make the number $10 higher we’ve avoiding discussing underwater payments to pharmacies on brand name drugs which we promise to revisit at a later point (so forgive us for trying to simplify the math a little here).

Lastly, we need to know what kind of rebates Humalog can generate. Lucky for us again, this information came to light at the start of 2021 via the U.S. Senate Finance Committee’s investigation into insulin costs, where it was stated, “Eli Lilly prepared widely divergent rebate bids within a few months of each other for Humulin and Humalog to a commercial health plan in Puerto Rico called SIS (22%), Cigna (45%-55% depending on formulary placement), a PBM in Puerto Rico called Abarca Health (up to 54%), and Optum’s Part D business (68%).”

Eli Lilly is the manufacturer of Humalog, and if the offer of rebates years ago was 68% to one of the largest PBMs (pre-2020), it seems reasonable to assume those rebates were available until the end of 2023 (when the WAC list price decreases occurred). And in fact, based on what we know about the general growth of rebates over time and recent reporting on Lantus’ net price (another insulin), we would believe that number to be a conservative estimate for the sake of this analysis (which is roughly aligned to what we know about insulin prices in 2020-2021). To be clear, the WAC for Humalog didn’t change from May 2017 to December 2023, and a 68% value of the wholesale acquisition cost (WAC) equals $186.80 today based on the $274.70 list price, leaving Humalog’s estimated net price at $87.90 (what we feel is a conservative estimate).

Crunching the numbers

With those assumptions out of the way, and our data points gathered, we can re-construct our Money from Sick People Model #1 that demonstrates how the cost for insulin is generally experienced by people with diabetes over the year, as well as the rebates that PBMs, rebate aggregators, and/or health plans are recognizing on each prescription of Humalog. Note, we are grouping PBMs, rebate aggregators, and health plans together in our model because it is largely irrelevant which entity is taking the money, and well, they’re increasingly the same organization. We construct this model again because we used a different insulin the first time around and just want to make sure the previous learnings from Lantus hold true for Humalog too (spoiler: they do).

Once this model is constructed, we can then compare the existing flow of money for Humalog relative to the 340B Covered Entity provider experience. From there, we analyze the impact of shifting the after-the-fact Humalog rebates from the health insurer/PBM/rebate aggregator to an upfront discount to a healthcare provider through the 340B program. And boy, does it change the Money from Sick People Model in meaningful ways (except for maybe the patient).

Results

We start by reproducing the Money from Sick People experience for people getting insulin through their traditional health insurance plan without any of the complicating factors that 340B can add into the transaction, meaning the chart below demonstrates the typical flow of money for the purchase of Humalog under commercial insurance. As can be seen in Figure 3 below, although Humalog is a different insulin from our November 2021 rebate analysis (which used Lantus), the results are more or less the same. PBMs/insurance companies/rebate aggregators actually make money on people getting their insulin filled thanks to drugmaker rebates, deductibles, and cost sharing. As can be seen below, the health plans pay out (Column [C]) less than they collect in rebates (Column [F]); ergo money made (Column [G] is reported as a negative number, reflecting lower costs than what was paid out).

Figure 3

Source: 46brooklyn Research

While the results of Figure 3 are expected – patients paying $1,802.52 for a drug that their plan/PBM receives $747.67 in profit for – it is a nice form of validation for our prior work with Lantus that the Money from Sick People moniker was appropriately applied to how rebates are generated and flow within traditional commercial pharmacy transactions.

With this confirmation in hand, we can move forward with re-imagining how the flow of dollars works when a 340B Covered Entity is dispensing the insulin to a person with insurance (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Source: 46brooklyn Research

In reviewing Figure 4, there are some things that may stand out – some columns changed a lot where others didn’t change at all. So let’s review each of the columns individually and why the math looks different from Figure 3.

Column [A] shows the Acquisition Cost. For a 340B Covered Entity, Eli Lilly has indicated they can acquire the drug at $0.10 per vial. This is sourced from the drug manufacturer who undoubtedly knows what the price is. At 10 cents per vial, Covered Entities are paying effectively 100% less than the normal cost to acquire insulin by non-340B pharmacies.

Column [B] shows the Patient Cost for the vial of insulin. Patients in plans with the typical deductible are going to pay the full drug cost until their deductible is met. Thereafter, they’ll pay their cost share (which we’ve estimated based upon prior analysis of patient costs for insulin). We feel this number, if anything, is an underestimate of typical historic costs for insulin (i.e., before the $35 cap). At least one study found an average cost of $63 per fill.

Column [C] shows the Health Plan Cost. Health plans share in drug costs in the manner that they normally do, regardless of whether the provider is within or not part of the 340B program (not paying while the patient is in the deductible phase, and picking up their share relative to the patient’s copay/coinsurance after the deductible is reached).

Column [D] shows the 340B Covered Entities’ Revenue off the sale of this medication. This amount is a function of both the patient’s costs [Column B] and the health plan’s costs [Column C]. Charging full commercial rates to someone for something you bought for pennies, it turns out, is pretty lucrative.

Note several states have enacted legislation that says that PBMs and health insurers cannot disparage 340B provider reimbursement (meaning that providers of 340B medicines cannot receive lower reimbursements than other market participants). As a result, we feel this column is fairly accurate to the average customer of the 340B entity (given that most people have drug insurance since the Affordable Care Act).

Column [E] shows the Margin made by the Covered Entity. Whereas on traditional, non-340B pharmacy transactions, we assumed that pharmacy providers were not making any money on Humalog (even though evidence from Medicaid data suggests maybe they were losing money with average payments of $262 per vial), here again we’re seeing 340B Covered Entity pharmacy providers actually making a lot of money, because they’re not really paying anything material to acquire the drug.

Column [F] shows the PBM/health plan’s rebate, which for 340B claims is non-existent due to duplicate discount prohibitions.

Note that effectively all contracts between manufacturers and PBMs/insurers preclude claims acquired at the 340B price from paying a back-end rebate (if the manufacturer is providing a front-end discount to the provider, then the PBM can’t also harvest a back-end rebate from the manufacturer on the same claim), so we assume the insurer doesn’t get their money from sick people (because the Covered Entity has captured it first). At a federal level, duplicate discounts between Medicaid rebates and 340B discounts are statutory (42 USC 256b(a)(5)(A)(i)), but in the private marketplace, the delta is generally a function of the contract. As way of proof, in Figure 5 we provide a screen shot of the rebate guarantee language in the City of Mesa, Arizona’s contract with their PBM (which precludes rebates on 340B claims). This type of exemption language is industry standard, and if you find a PBM contract that doesn’t have this, please let us know. So again, from the health plan’s perspective they’re not expecting a rebate from the claim acquired at the 340B price.

Figure 5

Source: City of Mesa, Arizona

Column [G] shows the Health Plan’s net cost. As their cost is no longer reduced by rebates, the health insurer/PBM doesn’t collect any rebates (money off the sick person) anymore and pays effectively half the drug’s cost over the course of the year (i.e., the real value with insurance related to this drug).

Column [H] shows the Net Cost of the Drug from the Manufacturer’s perspective. The drug manufacturer sells the drug for $0.10, and that is all they make per claim.

We should acknowledge that the above Figure 5 assumes that the Covered Entity has an in-house pharmacy who is dispensing the medication. That is not always the case. Most Covered Entities are hospitals, and not all hospitals have outpatient pharmacy services. However, the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) states that a Covered Entity can partner with an unlimited number of contract pharmacies to help Covered Entities stretch their scarce federal resources as a means of cultivating 340B spreads that go beyond the traditional footprint of the Covered Entity.

For you Mandalorian buffs, you can think of contract pharmacies as bounty hunters – hired contractors meant to expand the reach of a search for wanted assets. And of course, with every successful 340B bounty collected by a contract pharmacy on behalf of a Covered Entity, the rewards can be quite handsome.

So what does it look like when a Covered Entity uses a contract pharmacy to dispense the medication (and not an in-house pharmacy)? And how does this relationship alter the financial picture of the transaction?

Well, we have at least one contract-pharmacy-to-Covered Entity contract in the public domain. As can be seen below in Figure 6, the Jackson Memorial Hospital agreement presumes that a contract pharmacy who works with the Covered Entity will get paid a $65 dispensing fee for doing so and will get to keep a whopping 15% of the revenue from the prescription (note, this is the best 340B contract pharmacy revenue share we’ve ever seen based upon our channel checks, so this may over-estimate the typical experience at a contract pharmacy).

Figure 6

Source: Jackson Health System Public Health Trust Board of Trustees

If we modify the 340B model to include the contract pharmacy relationship (based on the above contract example), we get the following flow of money for our Money from Sick People model (Figure 7).

Figure 7

Source: 46brooklyn Research

If in looking at Figure 7 above compared to the previous one makes you ask the question, “Why on Earth would a Covered Entity give all this value ($3,296 Covered Entity Revenue compared to $2,021 Covered Entity Revenue) away to contract pharmacies?”, the answer is perhaps simpler than you think.

The mechanism of 340B Covered Entity to contract pharmacy actually functions retrospectively in most instances (i.e., a bounty hunt). Software companies like Macro Helix, Rx Strategies, Verity Solutions, and others analyze pharmacy claims activity at the end of each day for 340B claim eligibility. Claims that are found eligible at the contract pharmacy through these companies’ algorithms effectively transfer ownership of the claim from the contract pharmacy to the Covered Entity with the Covered Entity replacing the utilized inventory for the contract pharmacy.

In other words, the contract pharmacy gets its inventory replenished (i.e., no loss of value) while at the same time getting paid a big fee for sharing the data with the Covered Entity for them to claim the prescription. If the prescription isn’t captured in the 340B web, then the provider stands to effectively make no money off of it (see Figure 3; typical pharmacy margin for brand insulin is effectively $0, especially considering we rounded up) and the Covered Entity will make no revenue (the prescription isn’t associated with their 340B activity; ergo can’t be acquired at 340B prices). From the perspective of the Covered Entity, it is better to split the revenue than miss it entirely, which is why they are willing to pay big bucks for added 340B claims. (For those interested in more details on 340B contract pharmacy replenishment models, click here)

So we realize that was a parsec of information condensed into Jawa-sized stream of text, so let’s pause to unpack a bit.

First and foremost, rebates and statutory discounts tied to drug list prices are worth a lot of money. The examples above with 340B prices give us an appreciation for what “best price” practically means. Even getting a 68% rebate (i.e., commercial insulin rebate experience) can’t compare to purchasing the drug upfront for effectively 100% off the list price. The difference between a net price of $87 dollars for Humalog compared to $0.10 to Humalog is effectively an 800-fold decrease.

To be clear, we know how impactful Medicaid’s “Best Price” rebate is thanks to analysis from the Medicaid and CHIP Payment Access Commission (MACPAC). From the MACPAC Trends in Medicaid Drug Spending and Rebates presented in October 2022, we see that brand drug claims in Medicaid are effectively reduced by 60% via rebates – the majority (67.2% of brand claims) of which are priced via their “Best Price.”

Figure 8

Source: Medicaid and CHIP Payment Access Commission (MACPAC)

Recall Medicaid rebates are effectively the upfront discount available to Covered Entities (the Medicaid discount is equal to the 340B ceiling price). Covered Entities are effectively buying brand drugs for $40 what others pay $100 for, according Figure 8 above. That is a huge statutory advantage on drug costs; immense savings on what drugs cost to these groups.

To demonstrate, imagine two pharmacies across the street from one another. Each pharmacy has three patients who get a prescription of Humalog filled a month (say one vial each per person, per month). One pharmacy is getting Humalog at the 340B acquisition price, and the other is getting the normal pharmacy market acquisition cost. Over the course of the year, the non-340B pharmacy will need to invest $10,000 in inventory to stock the Humalog for their customers ($274 per vial * 3 vials per month [1 vial per patient per month] * 12 months in the year = $9,864). The 340B provider will need to invest less than $5 for the same amount of inventory for their customers ($0.10 per vial * 3 vials per month [1 vial per patient per month] * 12 months in the year = $3.60).

Arguably, that is what is meant by the phrase “340B Savings” (although the phrase is often used to lump both the upfront discount and the revenue made off selling products relative to this discount). A 340B Covered Entity needs to invest far less in their drug inventory costs than other providers, enabling them to use their money more efficiently.

Consider that for a hypothetical $10,000 investment, a 340B Covered Entity could effectively open 2,000 pharmacy locations that offered insulin compared to the one pharmacy location whose buying the drug the normal way. Said differently, how do we expect the “normal way” pharmacy claims are transacted to compete against such a system? That is a big competitive advantage alone. We emphasize this point because the savings alone are a valuable business commodity associated with lower carrying costs conveys major competitive advantages on its own.

The fact is that the goal of the 340B Covered Entity is to sell their cheaply acquired drugs at typical market rates (as evidenced by state legislative activity that seeks to enforce non-disparagement clauses against 340B providers) and they (Covered Entities) are positioned to use “340B Savings” to actually generate massive “340B Revenues.” Thus, there are significant economic disparities between Covered Entities vs. traditional non-340B pharmacies when it comes to the underlying investments needed to make in drug inventory for their respective businesses, but if you layer on payment which effectively makes one entity a lot of money, and the other very little, then the starting competitive advantages will compound into a race that a traditional pharmacy business cannot win.

To demonstrate, imagine both pharmacies receive $274 per prescription of Humalog they sell their customers, regardless of which business we shop at. Both businesses will make $9,864 per year for their three customers on Humalog ($274 per vial * 3 vials per month [1 vial per patient per month] * 12 months in the year = $9,864). However, the Covered Entities’ margin, relative to their drug acquisition cost, will be 99.9365% whereas the traditional non-340B pharmacies margin would be 0%. Which business would you invest in, if you could?

Now, Covered Entities like to point out that 340B savings/revenues are needed in order to “stretch scare federal resources as far as possible,” but given the amount of money in play, it seems worth questioning just how far these dollars stretch. Consider this: For every one person with insurance who a Covered Entity charges the full price for, they can give away the drug for free to around 2,747 individuals. (In the figures above, the profit per prescription is $274.70 relative to a cost of $0.10; ergo, 2,747 people can be served off the profits of one prescription; when using a contract pharmacy, the ratio is roughly 1,600-to-1). The ratio of those in need for prescription drug support to those not in need is not thousands-to-one. At worst, we’ve seen studies which suggest 36% of Americans report that paying for prescription drugs has been difficult to somewhat difficult. And while that number is almost certainly too high, it doesn’t raise to the level of 2,747-to-1, which raises another point. The 340B revenues made off insulin are likely cross-subsidizing other services at these Covered Entities.

Covered Entities, such as local community hospitals, are absolutely heavily investing in their local community’s well-being. Many of the dollars harvested through 340B spreads are going to legitimate, needed care – that’s why the program exists. But the flow of money in the 340B program isn’t transparent (we’re not aware of many other analyses of the flow of dollars like this) and highlights the frankly predatory role that Money from Sick People plays in a pharmacy claims transaction – whether it is a retrospective rebate or a massive upfront discount. In a rebate-driven system, the person producing the thing of value is not directly benefiting from it.

How much more affordable would customers of Covered Entities have found insulin to be if people got it at $0.10 a vial for the last decade or more? We recon, based upon the historic challenges with insulin affordability, a lot would have benefited from lower insulin costs. And to give a sense of scale, consider that more than half the hospitals in the country are 340B Covered Entities and that effectively half of all pharmacies (32K out of an estimated 66K) are 340B contract pharmacy locations. So it seems like there was ample opportunity for one or more of those involved in the 340B program (manufacturer, Covered Entity, contract pharmacy) to offer these savings to more patients than those that got them (and undoubtedly, some got free or reduced cost insulin that otherwise wouldn’t have). Which raises a bunch of questions regardless of what, or who, money from sick people actually benefits.

Unpacking the impact of rebates and 340B “savings” on patients

In reviewing what has been learned from examining insulin prices over the last 10+ years, we feel that it is clear that a lack of real price transparency has led to a pretty distorted drug pricing system. Whether the lack of transparency is the value of the rebate or the purchase discount, insulin truly exemplifies drug pricing dysfunction in that the people who need it are often paying more for it than makes sense. Consider, much as we did the first time when we reviewed Money from Sick People, that if the net price of Humalog (i.e., $87.90 for the drug plus a $10 dispensing fee for the dispensing pharmacy) was recognized up-front (i.e., at the point-of-sale), the patient would pay less money than they did through their insurer – who captured rebate value the patient didn’t fully see.

Figure 9

Source: 46brooklyn Research

In this hypothetical model (Figure 9 above) – where the patient receives the benefit of the rebated net price – the patient never reaches their annual deductible of $1,600 (though previously they reached it just halfway through the year), and the insurer/PBM actually recognizes no cost associated with insuring this drug.

While one might typically assume that this would be a dream scenario for a health insurer/PBM – they collect a premium, provide zero dollars in patient support, while the patient pays the full freight for their medicine – the truth is that they would much prefer the rebate model shown in Figure 3, where the health insurer/PBM collects a premium, provides zero dollars in patient support, and collects $747.67 in additional profit to top it all off. Not a bad day at the office.

But what happens when we stir a little 340B into the transaction? Well, look no further than Figure 10 below.

Figure 10

Source: 46brooklyn Research

In Figure 10, we perform the same theoretical shift we did with rebates to the 340B experience (where the patient pays the net cost up-front plus a $10 dispensing fee). We again see that the patient pays far less for the drug over the course of the year; however, the provider (in this instance, a Covered Entity) makes far less money off this arrangement than the previous one – even if $10 in margin relative to a $0.10 acquisition cost is still a 100% margin (it’s just not the couple thousand it was previously). As with the traditional health plan-rebate experience, this shift of value to the patient at the point-of-sale leaves the Covered Entity worse off than before, with less money to re-invest in other areas. However, that is more proof that Money from Sick People (rebates, statutory discounts, other terms) is exactly as described – the thing of value is used to benefit someone or something besides the person producing it. Which ultimately begs the question:

Why do we put up with a system that soaks sick patients for discounts that benefit others?

Comparing the myriad scenarios through the lens of a patient grappling with the intricacies of Humalog pricing, it becomes glaringly apparent why countless individuals find themselves ensnared in the relentless struggle of insulin costs and the precarious practice of rationing their medicines. Despite the ostensibly low net costs prevalent in today's healthcare system – be it through insurance coverage or the 340B Covered Entity framework – a disconcerting question looms: why is it that those in dire need of the drug remain oblivious to the complete value of the rebates or discounts tied to their life-sustaining medication? Is there anyone in whom these vulnerable patients can safely entrust their metaphorical “thing of value” (be it a rebate or discount)?

If we give the value to the health plan/PBM, their incentives seem obvious (and we should trust businesses to follow their incentives). If they expose the full value of the rebate, the business’ cost rise. Add to that, if they’re not using rebates to lower premiums, and their competitors are, they’re potentially going to struggle to sell their products to more customers. Medicare itself acknowledges that rebates serve either to lower premiums OR lower patient drug cost sharing. And thanks to the Government Accountability Office, we know which side is winning out: Medicare beneficiaries paid four times more for highly-rebated drugs than their health insurance plans did in 2021.

The reality is that every rebate dollar directed towards lowering premiums is a dollar not directly recognized by the person whose drug therapy produced it.

Simultaneously, entrusting the “thing of value” to the provider, particularly the Covered Entity, raises reasonable skepticism about tangible advantages for the patient. Paying the full cost to an entity that obtained the drug at a discounted rate resembles paying Gucci prices for Dollar Tree items. The critical distinction lies in the gravity of the consequences; exorbitant luxury prices may not be life-threatening, but the unavailability of insulin certainly is. The so-called “340B savings” touted by Covered Entities does little to alleviate the individual patient's financial burden for their medicine, a concern shared by approximately 30% of the US population. While some may experience sporadic relief through cross-subsidization – obtaining discounted drugs during financial crises when the Covered Entity extends charity care – one must question if this is fundamentally different from rebates lowering premiums.

No matter the perceived value of the trade-off, the harsh reality remains: when patients don’t receive the benefit of drugmaker discounts, the patient is the source of the generated subsidy that is harvested by someone or something else.

At the end of the day, we feel that the learnings from money from sick people are pretty clear – and aligned to what we said when we started 46brooklyn nearly 5 years ago - the drug supply chain is unhealthy for the patients who need it most.