Generic Truvada costs less than a dollar. Here's why you're likely paying much more.

After years of anticipation and a late 2020 patent expiration, generic competition to Gilead Sciences’ Truvada, one of the backbones of HIV treatment and prevention, finally appeared in late March 2021. As reported by the TRADEOFFS podcast last month, within 48 hours of multiple generic manufacturers entering the market, the cost for pharmacies to acquire emtricitabine and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), aka generic Truvada, had dropped more than 90% from the brand’s list price (i.e. wholesale acquisition cost [WAC]). However, this announcement, while welcomed, may miss a key point: will patients actually see these generic savings at the pharmacy counter? Or, as is too often the case in our non-transparent drug-pricing system, will the various layers of the drug supply chain (i.e., wholesalers, pharmacies, PBMs, insurers) arbitrage the historic price memory of Truvada to make a quick profit?

Let’s begin by providing some context for why this drop in pharmacy acquisition cost occurred at such a rapid pace. Within the last two days of March, eight different generic drug manufacturers brought competing versions of generic Truvada to the market. These eight started competing with Teva’s first-to-market generic, who until late-March had the generic Truvada market cornered thanks to their 180-day exclusivity rights. Moving to April, two more generic drug manufacturers jumped into the fray, bringing the total number of competitors up to 11 (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Source: 46brooklyn Research, derived from Elsevier Gold Standard Drug Database (GSDD)

That’s a lot of generic competition to materialize – from literally none (i.e., only Teva’s generic version) – in one month! As such, a 90% decline shouldn’t come as much of a surprise. If anything, with more than 10 manufacturers producing generic Truvada, perhaps the real surprise is that the decline in its cost to acquire was not steeper than 90%. Recall in July 2019, we found that the release of generic Lyrica yielded an eye-popping 97% discount to the original brand product.

Figure 2

Source: FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER)

According to the FDA’s own research (Figure 2), when there are more than 10 generic producers of a drug, the median generic-to-brand price ratio for AMP, or average manufacturer price (i.e., the price at which wholesalers acquire a drug from drug makers), and invoice-based wholesale price (i.e., the price at which retail pharmacies acquire a drug from wholesalers, before rebates) was just 1% and 2.2%, respectively. If we apply this FDA-observed ratio to Truvada (which carries a WAC list price of roughly $1,840 per month), that would indicate that pharmacies should be able to acquire generic Truvada at just $40 per month supply ($1,840 x 2.2%). At least that would be the cost if generic Truvada behaved in line with the median pricing dynamics of all generic drugs with 10+ manufacturers.

It turns out that producers of generic Truvada one-upped the median 10+ competitor generic drug, driving generic Truvada’s pharmacy acquisition cost down to below a dollar per pill. How do we know? Well, it’s far from elementary, but let us explain.

Consider the following snapshot from an e-mail that we received towards the end of last month from one of the smaller “secondary” drug wholesalers, listing a generic Truvada cost of just $17.29 per 30 count bottle (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Source: Marketing email from secondary wholesaler

We realize this is just one data point, but you must understand that the competition amongst smaller secondary wholesalers (those suppliers pharmacies have to purchase drugs outside of their prime wholesale vendor contract) is fierce; meaning that there is a good likelihood that this is representative of a competitive price for generic Truvada. To verify this, we wolfed down our chipped-chopped ham, wiped our mouths with our Terrible Towels, and phoned our good friends at Blueberry Pharmacy, a radically transparent cash pharmacy on the outskirts of Pittsburgh and asked them in our best Pittsburgh Dad voice, “what’s yinz payin’ for generic Truvada, and what’s yinz chargin’ patients n’at?” Their response is provided in Figure 4.

Figure 4

Source: Blueberry Pharmacy

As shown in Figure 4, Blueberry’s acquisition cost (which includes a 5% markup) is $14.69 per month supply (30 pills). Add in the cost of the lid, vial, label, etc., along with a $10 dispensing fee, and the patient can walk out the door with their month supply of generic Truvada for just over $25. If you enroll in Blueberry’s subscription model, that all-in cost drops to just over $18 per month supply. This is less than 1% of the list price of brand-name Truvada.

Now, we offer this example not as an advertisement for Blueberry Pharmacy (although we do love what they’re doing), but to offer a view into a parallel universe where the big middlemen are stripped out of the U.S. drug supply chain, giving patients access to medications in line with their true cost. This is all that Blueberry is doing. By jettisoning insurance, it is freeing itself from the warped incentives of today’s U.S. prescription drug supply chain that are in place to keep drug prices high, and instead, simply pricing drugs at a transparent markup to their cost and passing through all benefits of generic deflation to their customers.

The specific distortions we’re talking about here are the current pharmacy reimbursement practices, which when set by pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) are the lesser of what the pharmacy would charge (known as usual and customary or U&C) and what the PBM is willing to pay (for generics this is maximum allowable cost or MAC).

46brooklyn Tangent Alert

The prevailing practice of “lesser of” reimbursements that include a pharmacy’s cash price makes a whole lot of sense on its surface, but breaks down when you start to consider that there is no floor or ceiling for PBM reimbursements. Meaning that PBMs pay variable rates for generic drugs with pharmacies largely left in the dark as to how a rate is set. This creates an issue for pharmacies where in order to accept insurance, they must accept that some reimbursements will be higher than their cost to acquire drugs, whereas others will be lower. As with any business, pharmacies will seek out the higher reimbursements – particularly if they need to offset losses incurred on “underwater claims” – prescriptions dispensed below costs. Over time, we have observed that the amount of claims paying below cost has grown, making pharmacies increasingly reliant on the subjectively assigned high-margin drugs. This in turn diminishes their ability to set lower their U&C prices because they cannot afford to forgo these high-margin claims without risking the overall operations of their business. 46brooklyn’s co-founders recently explored this dynamic in the state of Massachusetts, which you can read more about here. Tangent over.

All of this means that cash pharmacies like Blueberry are rare, as most would lose an overwhelming majority of their patients if they thumbed their nose at accepting insurance (that said, some others out there we’re aware of are Freedom Pharmacy in Ohio and ScriptCo in Texas). And given what we just talked about, the fact that patients should only be paying $18-25 per month for generic Truvada – but are not – is not surprising given that these cash-only pharmacies are so rare. Instead, patients are left with pharmacy sticker prices that look nothing like generic Truvada’s true acquisition cost, as they are all in some manner being inflated thanks in large part to the incentives laid out by intermediaries like PBMs rather than directly pinned to the market-clearing price set by the competitive generic drug marketplace. So what is the price for generic Truvada?

“The game is afoot” - Sherlock Holmes

Unfortunately, PBMs in general are not interested in revealing the methods they use to price generic drugs (i.e., maximum allowable cost, or MAC) and not many (read, none) are offering to share their MAC prices with us at 46brooklyn. Instead, we have to rely upon intermediaries of the PBMs to get a sense for what the PBMs are paying for generic Truvada.

Take GoodRx for example. According to GoodRx’s initial filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission (called a form S-1), GoodRx, “primarily earns revenue from its core business from Pharmacy Benefit Managers [PBMs] that manage formularies and prescription transactions including establishing pricing between consumers and pharmacies.”

Digging a bit deeper into this document unearths additional detail on their value proposition to the PBM:

“PBMs aggregate consumer demand to negotiate prescription medication prices with pharmacies and manufacturers. PBMs aggregate most of their demand through relationships with insurance companies and employers. However, nearly all PBMs also have consumer direct or cash network pricing that they negotiate with pharmacies for consumers who choose to purchase prescriptions outside of insurance. We provide a platform through which PBMs can drive incremental volume to these networks by offering their discounted prices to our consumers. We expand the market for PBMs by increasing their cash network transaction volumes and by adding new consumers to the overall prescriptions market, many of whom, both insured and uninsured, would otherwise not fill their prescriptions because of high deductibles or prices. For many of our PBM partners, we are their only significant direct-to-consumer channel.”

Here’s how to interpret this paragraph (enhanced with the knowledge we have gained through our work).

First, you must know there is no single market-based price that employers/payers pay for generic drugs. Rather, prices are set based on contracts between PBMs and employers/payers, which means that prices can vary widely from one payer to the next. The one common thread between these contracts is that they most commonly price generic drugs as a discount to their Average Wholesale Price (AWP), which is yet another pricing benchmark in the alphabet soup of drug pricing acronyms here in the U.S.

We’ve told you all about how bogus AWP is in our prior writing, so you shouldn’t be surprised to learn that all 11 producers of generic Truvada have set their AWP at roughly $2,100 per month supply (30 pills).

That’s right – they set the list price at thousands of dollars, and then turn around and sell it to wholesalers at less than 1% of that price.

This $2,100 number is the one off which your employer (if you have insurance) gets its discount (or a pharmacy uses to set its U&C price). Let’s say it’s an 80% discount to AWP. That would put your employer’s price at $420, which is clearly a horrendous price compared to generic Truvada’s real cost. And guess what; if you are in the deductible phase, that horrendous price is the price you will end up paying out of your own pocket!

Now that we’ve reviewed the AWP-based games, we are left asking why would a PBM price product like Truvada in this backwards way; relying upon a fake price like AWP for its primary customer base, insurers?

“When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth?” - Sherlock Holmes

What GoodRx is saying in its S-1 is that if a patient is presented with this inflated price at the pharmacy counter, he/she “would otherwise not fill (his/her) prescription).” So, what is a PBM to do? How do they get the patient’s price-sensitive business, without killing their golden AWP-driven commercial-insurance goose? Simple. They invent a different price, what GoodRx refers to as “consumer direct or cash network pricing” for cash-paying patients and present them to you, the patient, either through their own “discount card” programs (e.g., Optum Perks – owned by Optum; Inside Rx – partially owned and operated by Express Scripts) or through a pricing aggregator such as GoodRx.

This allows a PBM to offer a different price to cash-paying consumers, to potentially capture that business without eating into their less price-sensitive, higher margin insurance business. Problem solved … for the PBMs that is. For those with high deductible insurance (which is most of us) and the employers footing the bill after we meet the deductible, this is yet another enabler of persistently high U.S. drug prices.

“Anderson, don’t talk out loud. You lower the IQ of the whole street.”

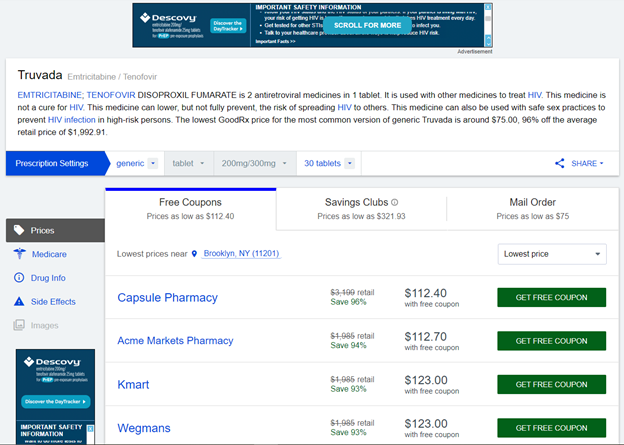

All that said, there is a key component of this discussion that may have gotten lost in this discussion. These “lower” discount program prices are still set by the PBM, which means they are not necessarily market-based prices. This may explain why, when we searched GoodRx as of May 17, 2021 for its lowest retail pharmacy price on generic Truvada, it was $112.01 (in Brooklyn, NY), rather than a cost closer to $30. If you are willing to receive the drug by mail, that price comes down to $75 (Figure 5).

Figure 5

Source: GoodRx (5/17/2021; Brooklyn, New York)

To be fair, this is still a sizable discount to Truvada’s brand drug price, and one you would be quite pleased with if you have been paying brand name prices over the last decade. Similarly, you’d probably be overjoyed at the GoodRx price after perusing the lowest 30-day supply prices offered by some other discount programs, which are positively terrible compared to GoodRx as of 5/17/2021 (Optum Perks: $1,606; Inside Rx: $1,105). While GoodRx easily jumps over the low bar set by some those inferior discounters, the reality is that when you go back to Blueberry’s transparent $25 non-member price for generic Truvada, even GoodRx isn’t even close to the real cost of the drug.

But there may be hope after all. Just this month, the company that has laid waste to supply chain inefficiencies across nearly every consumer facing marketplace we know – that’s right, Amazon (recall Mr. Bezos’ famous quote, “your margin is my opportunity”) – launched Prime Rx, giving Amazon Prime members access to discounted prices on drugs. Certainly with its immense power and leverage, Amazon would fry little Blueberry Pharmacy like a pierogi, right?

It turns out that the grand daddy of all retailers has leveraged their unparalleled scale and its laser focus on driving costs down for consumers to bring the price of generic Truvada as of May 17, 2021 down to (drum-roll please) …….

……

…...

…...

…...

$1,566.50 per month. (Figure 6)

Figure 6

Source: Amazon Prime Rx Savings (5/17/2021; Brooklyn, New York)

Huh?

In the announcement of their price look-up tools this month, Amazon’s VP of Pharmacy TJ Parker stated the following:

“While prescriptions don’t typically come with a ‘sticker price’ like face masks, or even saunas, you can now get pretty close with Amazon Pharmacy.”

While perhaps not his intended meaning, the morbid humor isn’t lost on these drug pricing nerds. Amazon Pharmacy is truly getting “pretty close” to the gigantic over-inflated sticker prices that are supposed to be “Ain’t What’s Paid” and sadly far off the mark of the true cost of the drug. Amazon Pharmacy’s member price for generic Truvada is more than 8,000% higher than little ol’ Blueberry Pharmacy’s.

Of course, scroll down to the bottom of Amazon’s Prime Rx page and you will find that their program is administered by Inside Rx (which as a reminder, is operated by Express Scripts).

In other words, this entire “disruptive” Amazon pharmacy entry seems to currently be little more than a white-labeled PBM discount card offering, with a price on this drug that is strangely higher than Inside Rx’s own price if you go directly to them.

Figure 7

Source: Amazon Prime Rx Savings

Another massive generic launch misses the mark thanks to drug supply chain distortions

Long story short, despite the Amazon narrative that this is “more Amazon and less pharmacy,” the status quo invisible hand of PBMs is everywhere, distorting generic drug prices even in places (and companies) that we have come to believe are saving us money. We see it in the AWPs set by generic drug manufacturers and the various prices offered by the competitor discount programs of GoodRx, Inside Rx, Optum Perks, and Prime Rx. But don’t be fooled, while the gray slash through the bogus list price on Amazon Pharmacy’s website and other similar discount sites might give you a false sense of comfort and save you money off inflated prices such as a pharmacy’s U&C in the short-term, they are a far cry from Blueberry’s generic Truvada’s cost and could cost us dearly in the long term if for no other reason than they reduce our collective sense of urgency to simplify drug pricing in this country.

So yes, today you can get generic Truvada for $112 through GoodRx, or use your commercial insurance and likely pay four times that much (at least). And if you’re a head of HR or a CFO staring at a PBM invoice from last month, this would seem like a great deal on Truvada compared to the nearly $2,000 you paid for brand-name Truvada. But the reality is these are just arbitrarily selected discounts off arbitrarily set list prices (Figure 8), which hides the true cost of the drugs that live underneath the stickers. Models like Blueberry show us that we need to expect more from our drug supply chain than this. If drug pricing worked as it should in this country, no one in this country would pay more than $30 for a month’s supply of generic Truvada right now.

Figure 8

Source: Amazon Prime Rx Savings, Blueberry, GoodRx, Inside Rx, Optum Perks, and data.medicaid.gov

But before we close this out, let’s not just stop with the pharmacy/discount card comparisons. Figure 8 further demonstrates how far reference-based pricing for prescription drugs still needs to go. If a tiny pharmacy with miniscule purchasing power can make an $18 member price or $25 non-member price work, we see clear evidence that our beloved CMS National Average Drug Acquisition Cost (NADAC) needs to more rapidly capture generic drug savings on new multi-source generics, as the NADAC price per pill is still $41 ($1,230 per month supply) as of May 19, 2021. Our long-time readers know why NADAC is elevated for this drug; NADAC is lagged by roughly two months, which means that all that generic competition that manifested on the final two days of March isn’t yet reflected in the surveyed costs. Next month will tell if the pharmacy savings start showing up in NADAC (we’d be surprised if they didn’t), but in so far as we rely upon NADAC to pay pharmacy claims in real time, we think that efforts should be made to get more comprehensive reporting and to reduce that lag. To be clear, NADAC is still a massive improvement over the broken AWP-linked status quo of most PBM contracts, but NADAC can, and should, be better.

But for the time being, at least in the sad state we find ourselves in the U.S., we are collectively being shielded from the true cost of drugs, which allows the supply chain intermediaries to soak up the excess money sloshing around in the gap between the prices it sets for generic drugs and the true cost of these same generic drugs. Unless we strip away these shields and demand greater transparency from our drug supply chain, we’ll have no chance of getting fair, market-driven prices for drugs like generic Truvada.

In the run-up to this month’s House Committee on Oversight and Reform hearing on drug prices featuring Tahir Amin, Craig Garthwaite, Aaron Kesselheim, and Abbvie CEO Richard Gonzalez, we appreciate Tony Hagen at the Center for Biosimilars and Richard Staines at pharmaphorum for featuring some of our pricing data in their pieces discussing list price changes on Humira.

Additional shout-out to Shuan Sim at Crain’s New York Business for highlighting some of our historical pricing trend analyses in his piece on the advancement of a legislative proposal in New York that seeks to create protections for patients from midyear formulary changes.

Lastly, thanks to Bob Weber, Administrator & Chief Pharmacy Officer at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, for featuring 46brooklyn CEO Antonio Ciaccia on his most recent installment of the Leadership Lessons in Health-System Pharmacy podcast.