The latest spooky, scary drug price changes

As a non-profit, we at 46brooklyn have made it our goal to provide insights into U.S. drug pricing data available in the public domain based upon the figures we’ve gathered over the prior month. This month is of course no different, except perhaps that drug pricing boogey men are out and about trying to use drug pricing to frighten, scare, and otherwise support their point-of-view. We’re highly skeptical of drug pricing pundits that offer opinions without facts, so per our monthly exercise, we offer our view of drug prices for September based upon the drug prices data facts we gathered over the last month.

The latest

Of course, to start with an analysis of drug prices, we first offer some context to consider when reviewing our learnings. This fall has been particularly rough, as a large portion of the east coast and several southern states has been hit by several natural disasters including hurricanes and tornadoes. These devastating events have not only affected many residents, but it has also hit the medical sector . In these times of crisis, healthcare providers are often relied upon to rise to the occasion and meet the unique needs of their communities in atypical ways. During tropical storms, hurricanes, and other natural disasters, pharmacists and pharmacy support teams are generally allowed to provide early prescription refills and special emergency fills under a state of emergency. This can lead to temporal increases in costs that should return to normal as refills return to regular schedules. At the same time, pharmacy locations that generally fill these prescriptions may not be open to fill prescriptions after the storm (and may never reopen, depending upon the business’ financial health, insurance, and a variety of other factors). This can result in shifts within the pharmacy network and the distribution of claims (such as those that were retail becoming mail). This could potentially impact NADAC surveys if a one or more pharmacy that normally responds does not or cannot as they pick up after these events. All of this is to say, be mindful of potential short term impacts of these real-world invents over the next few months.

In recent years, several natural disasters have caused production problems for pharmaceutical manufacturers such as those in Puerto Rico back in 2017 due to Hurricane Maria and most recently in North Carolina. As way of a more specific example of what we mean above, currently there is an IV solution shortage largely due to the recent hurricanes affecting Baxter production facilities. This IV shortage is leading to the delay of many surgical procedures across the country as Baxter continues to activate their global manufacturing network to help support patients and customers in the United States.

The FDA has authorized temporary importation for Baxter manufacturing facilities in Canada, China (two sites), Ireland, and the UK. The IV fluids that are most affected at this time include (but are not limited to) dialysis fluids, normal saline, various strengths of dextrose, as well as sterile water for injection and irrigation. To help with the situation, the FDA is also allowing compounders (and providing specific guidance on how to do so) to help fill the gaps from the impact of Hurricane Helene on Baxter’s North Carolina facility.

At 46brooklyn, we are no stranger to drug shortages and what that means long term for access and affordability. Drug shortages can often lead to increased drug prices, so we can anticipate that over the next several months, we may start to notice drug price increases for IV solutions and any other medications potentially affected by the most recent natural disasters as production continues to ramp up. In the meantime, the federal government has already put companies on notice that price gouging for essential medical supplies like IV solutions will not be tolerated. Of course, there may be other reasonable contexts to consider, but these things were what were top of mind as we reviewed the data.

The Cliff Notes

That said, there were a net 18 brand drug list price increases in September, with price changes impacting relatively infrequently utilized products, like Xopenex HFA ($108k on the low end of gross prior year Medicaid expenditures [PYME]), up to more meaningful medications with a lot of annualized expenditures like DARZALEX Faspro ($161 million in PYME). As in months prior, we see prices changes all over the board – some of which can be just a few hundred dollars, whereas others are hundreds of millions of dollars. In September, some medications have as low as a 3.0% price increase and as high as 14.5%. Depending on the price of a medication, even a small overall percentage increase could be substantial enough to be thousands or even millions of dollars compounded over time.

In September, not one brand medication took a list price decrease, which is interesting, as we usually see at least one medication each month that takes a tumble. And as we know, Wholesale Acquisition Cost (WAC) price changes can affect drugmaker rebates and discounts, therefore if the WAC of a brand medication goes down, often the rebates that the drug manufacturer offers go down as well.

Some of the biggest and/or most interesting movers to take note of for September 2024 were:

· Paxil and Paxil CR oral tablet (9.9% increase; $285k and $328k PYME respectively)

· Filspari oral tablet (9.9% increase; $3.6 million PYME)

· Addyi oral tablet (14.5% increase; N/A PYME)

· Venofer solution for injection (3.0% increase; $31 million PYME)

· Effient oral tablet (10.0% increase; $117k PYME)

Among the standout price increases are for medical conditions including depression/anxiety (Paxil/Paxil CR), blood clot prevention (Effient), a rare kidney disease (Filspari), hypoactive sexual desire disorder (Addyi), and low iron anemia (Venofer).

Although the percentage increase wasn’t high (3%) for Venofer, the dollar amount of expenditures potentially exposed to that increase is high ($31 million PYME), whereas, on the other hand, a 10% increase for Effient tablets only impacts a low amount of publicly-quantifiable expenditures ($117K PYME). Therefore, it is important to note that sometimes a small percentage increase – especially for an already expensive brand medication – can result in a significant bag of loot in PYME. Nevertheless, remember that these numbers are just part of the drug pricing context for these drugs. The figures presented above are the prices before drug channel mark-ups (hospital chargemasters, 340B providers, PBMs, GPOs, wholesalers, pharmacies, etc.) and more importantly, drugmaker rebates, which as we know are growing significantly over time and are at their largest amounts in the Medicaid and 340B programs.

On the generic drug side of the coin, year-over-year (YoY) generic oral solid price deflation is at 7.2%, as quantified by national average drug acquisition cost (NADAC). While there has been some online chatter on how some of the recent fluctuations are some sort of evidence of substantial flaw with NADAC, we’re not sure we agree, considering the benchmarks value relative to other distorted pricing lists. If, as some claimed, the major bouncing changes to NADAC were a result of recent methodology changes, then, all else being equal, the impact of those changes should have resolved (i.e., month-over-month swings cannot be reasonably explained by methodology changes that occurred once; the impact of those changes should have been felt only once, with a new normal moving forward). Rather, it seems more likely that other sources are responsible for NADAC’s recent zig-zags.

The most obvious cause of NADAC’s new “volatility", in our mind, is the impact of inconsistent survey participation. NADAC is a voluntary survey of retail pharmacy acquisition costs, and therefore NADAC reflects the voluntarily submitted data from who is purchasing drugs at what price. We know that pharmacies are not buying drugs under the same contract terms. Take for example, this recent Drug Channels analysis that says, “For smaller pharmacies, wholesalers’ sell-side discounts for brand-name drugs are typically linked to generic purchases.“ Conversely, this is an indicator that the purchasing environment for larger pharmacies is quite different. Product tying and cross-subsidization will create variability in purchases that can be exposed if say, the survey has been historically composed of a group with/without product-tying terms and new survey participants enter that have the opposite terms.

If NADAC survey participation has been historically weighted in the direction of the purchasing realities of small and mid-size pharmacy groups (where wholesaler off-invoice discounts and cross-subsidization are more prevalent), but then a larger pharmacy group enters the survey pool with a different purchasing reality, this can create the “data shock” that can take NADAC off its normal course. Further, if there is not consistent participation in the NADAC survey month-over-month from those new participants – where one month, there is a substantial infusion of one purchasing reality but another month where it is absent – the NADAC survey will reflect that those composition changes with the appearance of market volatility when in fact the cause of the data swings is really survey participation volatility.

Note that the largest drug wholesalers are akin to the largest PBMs in their market position (i.e., the Big 3 wholesalers represent 80%+ of purchases just like the Big 3 PBMs represent 80%+ of sales). Our work and others have found that reimbursement for the same drug is not uniform. We believe this reimbursement variability is a function of PBM approaches to pricing (i.e., variable MAC rates for generic drugs). It stands to reason if PBM intermediaries have this effect on reimbursements that wholesalers may reasonably be assumed to create differing experiences on the pharmacy purchasing side (akin to what PBMs create on the reimbursement side). Public access to pharmacy purchasing data is harder to get than access to reimbursement data by plans (for example, we can see different trends across the various state Medicaid programs, composed of different PBM operators, but cannot really see variability in purchases beyond what inferences we can make from CMS’ NADAC equivalency metrics). To be clear, if inconsistent wholesaler pricing sounds like an antitrust violation – that a seller would be creating differing prices for the same product to differing purchasing groups, well, some parties seem to already be suing the wholesalers over allegations such as these (see 10K disclosures). Make of that what you will – we’ll wait to see what if any learnings actually come out as those cases are litigated, refiled, or refined.

And, for what it is worth, from what our channel checks have told us, CMS self-assessed what was going on and knows the answer that variable survey participation is what is driving NADAC swings – NOT methodology changes (i.e., CMS was FOIA’ed for this answer). As such, it’s important to note that despite NADAC’s value over legacy PBM pricing benchmarks, it is not without its own limitations – some of which could be rectified by a more standardized and holistic approach to survey participation. And in case this isn’t explicit enough, for our pharmacy readers, if you are wondering how a large pharmacy organization can have such a dramatic impact on the NADAC survey results, remember this: PBMs aren’t the only ones responsible for community pharmacy financial pressures, and when large wholesalers tell you how much they love and value independent pharmacies, you should believe them.

With that said, it can be hard to know what drug pricing changes will occur from one month to the next, especially when it comes to medications that are subject to so many variables. As the spooky season is at its zenith, make sure to keep come back next month to see what tricks have occurred with price changes during the month of October. But for now, let’s take inventory of everything that happened last month.

What we saw from brand-name medications in September

1. A small number of brand drug list price changes

There were a total of 18 brand-name medications that saw wholesale acquisition cost (WAC) price increases in September, which is featured and contextualized in our updated Brand Drug List Price Change Box Score.

Price changes this month ranged from 3.0% to 14.5% and impacted $4.7 billion in gross prior year Medicaid expenditures (PYME). As a reminder, brand list price increases in Medicaid are largely held in check thanks to the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program (MDRP), which has mandatory discounts along with rebate penalties for drug price increases that occur faster than the rate of inflation. This is one of a number of reasons that solely analyzing brand list price changes provides an incomplete picture of what’s really happening with brand manufacturer economics, thanks to the growing lot of opaque rebates, discounts, and giveaways that drugmakers shave off those list prices. But alas, until PBMs, insurers, and rebate aggregators make more granular data on net prices public, we’ll continue working with what we’ve got.

2. Brand price trends over time

Figure 1

Source: Elsevier Gold Standard Drug Database, CMS State Drug Utilization Data, 46brooklyn Research

To help contextualize brand name drug list price increase behavior, we find it beneficial to review past trends. In comparison to the data from prior months of September, this year seems to line up almost identically with September 2023, which had 18 (combined increase and decreases) branded price changes. Looking at past trends, September, overall is a month where there have been consistently a small number of branded price changes.

The highest number occurred nine years ago in September 2015 with 44 net branded price increases, whereas the lowest is September 2021 when there were only seven price increases.

To put it into a more recent perspective, there were a net (increases and decreases) of 18 medications in September 2024, 17 in September 2023, 32 in September 2022, 7 in September 2021, and 9 in September 2020.

Moreover, of the drugs that took increases so far this year, the median price increase has been 4.5% – a percentage that has been holding steady without much fluctuation since 2019 (see Figure 1 or Stat Box #3 & #4 within the dashboard).

3. Brand drug list price changes worth taking note of in August

While we have thus far focused on the aggregate brand drug picture, next we identify specific brand drugs worth taking note of in a couple different ways. Primarily, we look for medications with a lot of prior year gross Medicaid expenditures (PYME). We next look for drugs with large pricing changes (+/- 10%). And finally, we look for drugs that are interesting to us either because we’ve previously written on them, they’ve recently been in the news, or because we find them of unique clinical value. This month, when looking for these drugs in the brand arena, we found several worth mentioning based upon these reasons:

Antidepressants

Paxil CR and Paxil (paroxetine) are selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) indicated for a variety of mental health disorders including anxiety, depression, OCD, PTSD, etc. These medications both took an increase in WAC of 9.9%, resulting in $328K and $285K in gross prior year Medicaid expenditures (PYME).

Kidney Disease

FILSPARI (sparsentan) is an oral medication used to slow kidney decline in adults with a rare kidney disease called primary IgA nephropathy (IgAN) for those who are risk for their disease getting worse. This medication also saw an increase in WAC of 9.9%, which resulted in an additional $3.6 million in PYME.

Blood Clotting Reducer

Effient (prasugrel) is a P2Y12 platelet inhibitor indicated for the reduction of thrombotic cardiovascular events (including stent thrombosis) in patients with acute coronary syndrome who are to be managed with PCI. Notably, this medication had a 10.0% increase in WAC, with a $117K in PYME.

Anemia

Venofer (iron sucrose) is an iron replacement product given intravenously and is indicated for the treatment of iron deficiency anemia (IDA) in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Notably, this medication had a 3.0% increase in WAC, resulting in $31 million in PYME.

Asthma

Xopenex HFA (levalbuterol tartrate) is a beta2-adrenergic agonist indicated for the treatment or prevention of bronchospasm in patients 4 years of age and older with reversible obstructive airway disease. This medication had a 5.0% increase in WAC with a $108k in PYME.

Other

Addyi (flibanserin) is a medication indicated for the treatment of premenopausal women with acquired, generalized hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) as characterized by low sexual desire that causes marked distress or interpersonal difficulty. This medication experienced an increase in WAC by 14.5%, resulting in a currently unknown increase in PYME.

Of course, our update doesn’t end with brand medications. While brand drugs represent the majority of payer costs, patients overwhelmingly take generic medications, which means we cannot overlook what is going on with them.

What we saw from generic medications in September

4. A relatively flat, unweighted price change picture

Each month, we start our evaluation of generic drug price changes by looking at how many generic drugs went up and down in the latest month’s survey of retail pharmacy acquisition costs (based on National Average Drug Acquisition Cost, NADAC), and compare that to the prior month. Basically, the quick way to read Figure 2 below is to look for orange bars that are taller than blue bars to the left of the line, and exactly the opposite to the right of the line. That would indicate a good month – more generic drugs going down in price compared to the prior month, and less drug prices going up.

Figure 2

Source: Data.Medicaid.gov, 46brooklyn Research

When you look at the bar graph on the left side you can see that the blue bars are almost non-existent compared to the orange bars (much different than in August). However, on the right-hand side, you can see that the blue bars are much higher than the orange bar except for the 0-10% increase bar (again much different than last month when the orange bars outpaced the blue bars). Therefore, in September you can see that there were not a substantial number of decreases in generic prices compared to August with the exception of the 0-10% range where 10,507 price cuts were seen, whereas in August, the amount of medication decreases for the same range was only 2,348.

To the right of the line, the September data is showing a larger amount of generic medications with price increases specifically in 0-10% range, resulting in 10,379 price increases. Conversely, in August, there were only 4,461 price increases in this same range. The 10-20% increase range was lower in September, with only 2,290 generic price increases compared to August, which had 6,564.

For every generic drug that increased in its NADAC price this month, 0.86 decreased in price (which is almost a wash from what normally gives us slightly clearer signals on an unweighted basis). As usual, take this unweighted price change analysis with a grain of salt. To really make heads or tails of all of these pricing changes, let’s weight these changes.

5. Weighted Medicaid generic drug costs come in at $15 million in inflation

The purpose of our NADAC Change Packed Bubble Chart (Figure 3) is to apply utilization (drug mix) to each month’s NADAC price changes to better assess the impact. We use Medicaid’s most recent year of drug mix from CMS to arrive at an estimate of the total dollar impact of the latest NADAC pricing update. This helps quantify what should be the real effect of those price changes from a payer’s perspective (in our case Medicaid; individual results will vary).

The green bubbles on the right of the Bubble Chart viz (screenshot below in Figure 3) are the generic drugs that experienced a price decline (i.e. got cheaper) in the latest survey, while the yellow/orange/red bubbles on the left are those drugs that experienced a price increase. The size of each bubble represents the dollar impact of the drug on state Medicaid programs, based on utilization of the drugs in the most recent trailing 12-month period (i.e. bigger bubbles represent more spending). Stated differently, we simply multiply the latest survey price changes by aggregate drug utilization in Medicaid over the past full year, add up all the bubbles, and get the total inflation/deflation impact of the survey changes.

Figure 3

Source: Data.Medicaid.gov, 46brooklyn Research

Overall, in September, there was almost $112 million worth of inflationary drugs, with an almost comparable offset of $97 million of deflationary generic drugs, netting out to approximately $15 million of generic drug cost inflation for Medicaid. These numbers are much smaller compared to last month’s report where we saw around $650 million of inflationary drugs with an offset of only $31 million for a net of ~$618 million.

The month-over-month increase bubble chart is almost identical compared to its counterpart, which has not been the case these last couple of months where we had reported either a large increase bubble or a large decrease bubble. So, for the month of September, the generic drug price decreases went up substantially, coming in around $97 million compared to August where we only saw about $31 million. This is a much more even view of the NADAC Change Packed Bubble Chart compared to the last couple of months (though as we said in our intro, that doesn’t necessarily stop NADAC critics from saying the sky is falling).

6. Year-over-year generic oral solid deflation at 7.2%

Ever since June 2020, we have been tracking year-over-year generic deflation for all generic drugs that have a NADAC price. We once again weight all price changes using Medicaid’s drug utilization data. This month, deflation on oral solid generics and all generics decreased to 7.2% and 6.7%, respectively (Figure 4). If you are a purchaser of generic drugs, an increase in this metric is ideal as it means costs are declining. Businesses generally enjoy it when their input costs go down. Historically, NADAC deflation numbers have been much higher than they’ve been recently; however, since April 2024, they have started to trend back up for the most part. The numbers for September’s data (like August) continue to be more in line with historical trends dating back to 2021. The percentages that we saw in July and May seem to be the exception and not the rule as the 20% and above range has not occurred in the last 3 years.

Figure 7

Source: Data.Medicaid.gov, 46brooklyn Research

For those of you who have followed what is going on with broader U.S. market inflation, understand that part of what we’re measuring here is a comparison to the trend in pricing a year ago. This means that some months will have easier comparisons relative to harder comparisons. The cycle of “easy” to “tough” comparisons is something that plays a roll in aggregate deflation/inflation over time. We haven’t seen others raise this point when using our graph (despite using it to highlight NADAC variability), so we bring it up now to be sure that we’re fully contextualizing what is going on with generic drug prices. In last month’s report, we tried to demonstrate with the month-over-month deflation how NADAC is a net march downward (even if it can bounce up and down sometimes). Don’t lose track of those facts when aggregating to a year basis (even if it isn’t as easy to zoom out). NADAC still is signaling that generic drugs are 7% cheaper than a year ago (if only all our inflation issues were trending in that way; we would be so lucky if our broader inflation fight followed generic drug deflation over the last year).

7. Top/notable generic drug decreases

While in July and August, the drug price decrease and increase bubbles were opposite of one another depending on which month you look at, in September, they are almost identical in size with the month-over-month decrease bubble being only slightly smaller. After reviewing the various sizes and colors that compromise this month-over-month decrease there are some notable decreases.

There are tons of generic drug price decreases this month with some being more interesting than others. Some of the biggest decreases continue to be ADHD medications (stimulant and non-stimulant), antiviral medications (Hep B, HIV, influenza, CMV), and migraine medications.

Over the last few months, we have seen ADHD medications decreasing in price (for the most part), and this month is no different. ADHD medications decreasing in price this month include dextroamphetamine/amphetamine ER 10mg, 15mg, and 20mg doses all decreasing by -17.1%, -19.3%, and -19.2% respectively.

Lisdexamfetamine 30mg and 70mg also decreased in price by -18.1% and -23.7%, which is interesting, as last month, the 40mg and 60mg capsules also went down in price.

Dextroamphetamine took the biggest decrease out of all of these medications, as it went down by -32.1%.

Other medications used to treat ADHD include atomoxetine 10mg capsule (a non-stimulant), which took a decrease of -39.8%, as well as the 40mg strength, which decreased by -6.2%.

A repeat offender from last month includes the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAID) lofena 25mg tablet, which took a decrease by -8.5% in September, and in August, it also took a decrease by -14.8%. So overall, in the last two months, this medication decreased by -23.3%.

Another notable trend is the decrease in price of antiviral medications used to treat either hepatitis B, HIV, the flu, and cytomegalovirus (CMV). Entecavir 0.5mg and 1mg are used to treat hepatitis B, and these medications had a decrease in price by -17.9% and -33.6 respectively.

Oseltamivir 75mg, an oral antiviral for the treatment or prevention of the flu, took a decrease by -10.4%. Oseltamivir is the generic of Tamiflu, which made the announcement in 2019 that it would be available over-the-counter but this has yet to be seen.

Valganciclovir 450mg tablet which is used to treat CMV decreased by -10.5%.

Migraine medications this month also are trending down with rizatriptan 5mg tablet decreasing by -25.1% and sumatriptan succinate 25mg tablet decreasing by -14.7%. The migraine drug market continues to grow according to reports from Research and Markets. Migraine medication utilization, especially generics, continue to trend up especially with telemedicine groups such as Cove focusing on this debilitating medical condition.

8. Top/notable generic drug increases

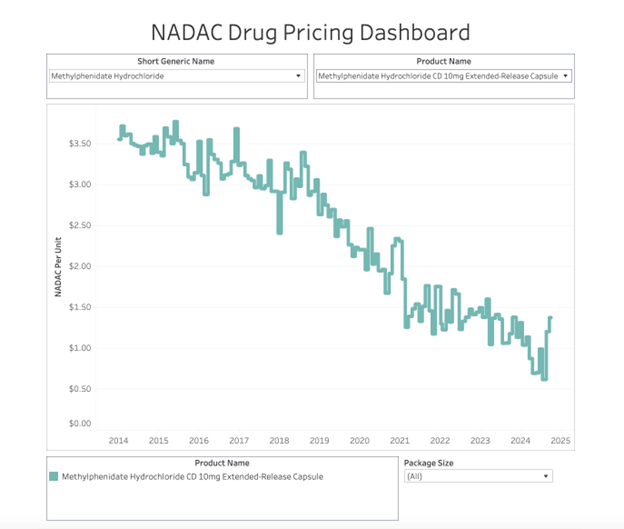

On the increase side of things, the most impactful increases of 50% or above were methylphenidate LA 10mg capsule (54% increase), methylphenidate ER (LA) 10mg capsule (54% increase), lamotrigine ODT 50mg (51.1% increase), carbamazepine ER 100mg capsule (57.3% increase), nitrofurantoin MCR 100mg capsule (53.3% increase), and acitretin 25mg capsule (50.9% increase).

It is interesting to see that while many ADHD medications are decreasing in cost, there are just a few that are increasing their costs, especially as ADHD medications continue to be a reoccurring drug shortage these last few years. Last month, we saw an increase in dextroamphetamine-amphetamine ER 10mg capsule by 63.7%, as well as methylphenidate LA 20mg capsule, which went up by 60.7%.

Both lamotrigine ODT and carbamazepine ER capsules are medications used to treat various types of seizures, while acitretin is used to treat severe psoriasis. Nitrofurantoin is an antibiotic typically used to treat urinary tract infections. Another dosage form of nitrofurantoin, the oral suspension, has been on the ASHP drug shortage list with a recent revision as of August 25, 2024, showing some manufacturers continue to have production setbacks. Now more than ever, it is important to understand (especially in times of crisis like with hurricanes) that drug shortages can cause the price of a medication to increase by 16.6%.

Another interesting note within the September data is that it continues to show that something is up with fluphenazine pricing. Fluphenazine is a first-generation antipsychotic used to treat mental health disorders. This past month, fluphenazine 5mg tablets increased by 43.2%, but last month they decreased by 52.2%, so between this month and last month fluphenazine 5mg tablets have actually only decreased by 9%. If you recall, two months ago we reported that fluphenazine 10mg tablets increased by 59.0%. Of course some of these ebbs and flows could be the result of the NADAC survey inconsistency, perhaps further demonstrating inconsistent acquisition costs for this drug between different pharmacy classes of trade.

That’s all for this month! Hope your Halloween consists of less banana flavored Runts and much more Take 5 bars. Come back next month to see which medication prices continue to spook us here at 46brooklyn.