How money from sick people works, Part II: The 340B story (Original)

A january unlike any other

In case you didn’t notice from our last report on new year price changes, at the end of December 2023, many insulin vials and pens took significant (i.e., 75%+) list price decreases. Given much of the early 2024 attention on brand drug list price increases, it bears repeating that insulins in 2024 are largely a quarter of the price they were in 2023. This cratering of prices for a number of high-profile brand products in unison with others (e.g. respiratory inhalers) is largely unprecedented.

The significance cannot be overstated. Arguably, no products have more exemplified the drug pricing dysfunction of the United States than insulins over the last 30 (and arguably, 100) years. As we are often reminded, the original insulin patent was sold for a $1 (even if the patent in question was essentially a patent for ground-up animal pancreas; US Patent #1469994).

Yet, despite insulin’s meager origins and the proliferation of diabetes diagnoses – which today impacts more than 38 million people in just the U.S. alone – thanks to congressional investigations, media reporting, manufacturer disclosures, and loads of research, we know that the real story of insulin pricing has become healthcare’s sad version of “Where’s the beef?”

Here at 46brooklyn Research, we too have used insulin as the bloated punching bag that it deserves to be. See, as list prices and net prices for insulin have diverged over the years, the full value of the growing drugmaker discounts were often not making their way to the end payer.

As such, we have focused on insulin as an example to demonstrate how rebates are really just “money from sick people.” This is because drugmaker rebates are little more than money collected by government programs, pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), rebate aggregators, insurers, and/or plan sponsors – on prescription drugs taken by sick people – that are often used for purposes other than lowering the cost of the medicine for that sick patient, like say to lower premiums for all people covered by the plan.

As we showed in 2021 (and as was expertly highlighted by USA Today at the time), the rebate system imposes great financial harm on those burdened with insulin dependency and the other corresponding costs associated with diabetes management. To quote from our 2021 report:

“What our models show us is that patients are over-paying for vital prescription drugs. In the current “Money from Sick People” environment, a patient expends $1,906.72 annually per year on Lantus alone (absent any premiums they have to pay, and without consideration for diabetic supplies they’ll need to use Lantus properly). The health plan’s total net expenses are -$1.078.72. That is to say, the health plan made around a thousand dollars off the sick patient’s drugs. They did this by collecting and banking rebates during the first four months of the year, and then using those rebates – plus the rest of the rebates that they generate over the remainder of the year – to pay for the expenses to the pharmacy to acquire and dispense the drug (and it just so happens that they have some money left over at the end).”

Because of the severity of the insulin pricing problem, we always intended to revisit it to demonstrate other ways money from sick people works. However, that will be more difficult with respect to insulin prices at least, now that they are significantly lower than their former inflated reality. So before drug pricing critics move onto the next shiny object and insulin fades into the rearview of our collective understanding of drug pricing dysfunction, as a result of these list price decreases (which also reduces the rebates they’ll produce), we invite you to join us in another look at how our system’s addiction to discounts distorts the marketplace and creates winners and losers among drug channel participants and end payers. With that, we give you: Money From Sick People Part II: The 340B Story.

The origin of the 340B program

Typically, when prescription drug rebates are discussed and debated, the common tug of war lives between drug manufacturers and PBMs. Because PBMs represent so many covered lives, drugmakers understandably want PBMs to cover the medicines that they produce. For medicines within competitive classes, PBMs can use their leverage to shake down manufacturers for big rebates in exchange for coverage and preferential treatment for those medicines. While this may lower the net prices of medicines relative to their list prices, it is often argued that the pressure for bigger rebates and other like-discounts disincentivizes manufacturers from lowering list prices, and in fact, could pressure them to do the opposite. This dynamic also arguably results in perverse incentives for PBMs, who stand to bring in more money off medicines with higher list prices (and higher rebates). Thus, you have controversies brewing at the federal level today where there appears to be tailwinds behind efforts to “delink” PBM compensation from the list prices of medicines.

While PBMs are getting their deserved moment in the sun for their role in distorting this marketplace and arbitraging drugmaker discounts, in fairness, they aren’t the only ones with their hands in the drug pricing cookie jar.

As many have probably heard, under the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), Medicare starts getting their own penalties and rebates from drug manufacturers. While the way the IRA goes about harvesting those rebates in Medicare my differ, rebates and special deals for government programs in the U.S. is hardly new. For those who don’t know, thanks to the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990 (OBRA ‘90), Medicaid programs also get their own rebates from drug manufacturers through the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program (MDRP).

Figure 1

Source: U.S. Office of the Inspector General

When Congress enacted the MDRP, they decided not to directly negotiate/set drug prices (like much of the rest of the western world); rather, they decided to obtain retrospective discounts off manufacturer-set list prices. An Office of the Inspector General (OIG) report in 1990 makes it clear (in our view at least) that brand price negotiation was under consideration at the time, but ultimately other controls (i.e., rebates) were selected.

What OBRA ‘90 did in establishing the MDRP was to set a formula to determine the Medicaid rebate amounts.

The formula states that Medicaid was due a rebate on the drug on the basis of: (1) A percentage of the drug’s price (not the typical wholesale acquisition cost list price, but average manufacturer price [AMP]) OR Medicaid would get the best price negotiated; and (2) Medicaid would get additional rebates if the price of a drug rose faster than inflation. Note that the law required manufacturers to report both the AMP and the “best price” to the government for the purposes of calculating the Medicaid rebate.

So while the government was not going to be involved in negotiating prices necessarily, they’d get the benefit of negotiated prices from the competitive market (via the “best price” provision), as well as the benefits of a penalty (a disincentive) to not raise drug prices too much (at least not higher than the rate of other goods and services). Regardless of the details, in practice, the precedent was set that Medicaid programs would be required by law to get the “best price” in the market.

As a consequence of this formula, drug manufacturers pulled back on purchase discounts offered to select healthcare providers (they didn’t want to give Medicaid the best price they were giving to providers).

Obviously a local hospital has a far smaller footprint than a state Medicaid program; so are we really surprised manufacturers acted in this way under this new law? The pull-back on drugmaker discounts to healthcare providers as a result of the MDRP best price obligations was seen as one of the unforeseen consequences of the policy, which birthed calls for adjustments in Congress.

So in 1992, Congress passed the Public Health Service Act. Contained within this act is Section 340B, which established a program whereby select healthcare groups (what we call Covered Entities) could purchase drugs cheaper than market rates – rates equivalent to what Medicaid got in terms of rebates.

The creation of the 340B program and its extension of government-mandated discounts to Covered Entities was a stealthy way for the balanced budget congressional Republicans of the 1990s to offer a new entitlement program at effectively no federal budget impact (at least on paper). By effectively stating, “providers, you can buy drugs at the same net prices we the government get for Medicaid,” they did not need to apportion any meaningful funding for the program, while at the same time, rectifying the problem in the minds of the impacted healthcare providers who got access to buy cheap drugs again.

To be clear, participants in the 340B program (i.e., Covered Entities and their affiliated partners) make money off the system the old fashion way – buying the drug cheap and selling it high. Because the 340B program is a discount on drug purchases, Congress effectively created a complex subsidy for 340B Covered Entities achieved through requirements imposed on drug manufacturers. Via the 340B program, Covered Entities are able to purchase drug inventory at a significant reduction in cost, beyond what they would otherwise negotiate in the typical commercial marketplace (i.e., “best price”). After securing low-cost inventory, which itself frees up the business’s carrying costs, Covered Entities rely upon the second source of their subsidy — privately insured individuals — to generate funding on these discounted drug purchases. This funding (i.e., the profit between sale price and purchase price – loyal 46brooklyn readers might be thinking of the familiar term, “spread”) enables Covered Entities to deliver care to the uninsured or underinsured. As stated within an old Health Resources and Services Administration’s (HRSA) Hemophilia Treatment Center Manual, “If the covered entities were not able to access resources freed up by the drug discounts when they apply for grants and bill private health insurance, their programs would receive no assistance from the enactment of Section 340B and there would be no incentive for them to become covered entities.”

So for those who were previously unfamiliar with the mechanics of Medicaid rebates and the 340B program, hopefully this gives a better understanding of how these government entitlement programs impact the drug pricing landscape. With the goals of Medicaid and 340B essentially concentrated on the noble purpose to provide healthcare for those who otherwise would not be able to afford it, the rub becomes how the programs go about achieving those ends — which is to draw its financial lifeblood from the list prices of medicines and the spreads harvested from patients and plan sponsors instead of more traditional budgeting means. And regardless of the return on investment received from Medicaid and 340B, the prevailing wisdom is that somehow, the yielded rebate dollars occur with no costs to the system.

Sounds all pretty amazing, right? We can fund big programs like Medicaid and 340B by just hitting up the drug manufacturers for discounts off their prices, and that way, it doesn’t cost the rest of us anything. And now with Medicare getting their own rebates, it begs a larger question: if we could just drive more discounts from drug manufacturers, what other sorts of cool stuff could we then get for free?

Of course, it doesn’t really work this way.

There is no secret drug money tree that keeps replenishing itself (outside of Woonsocket, that is). These discounts may not have a direct, easy-to-decipher cost on the front end, but somewhere, somehow, this money has an origin story.

And much like our Money from Sick People tale from 2021, the drug discounts that underpin the Medicaid and 340B programs don’t come without a cost either.

The old saying goes, “there’s no such thing as a free lunch.” So when it comes to 340B, let’s see who is getting to feast and who is picking up the tab.

First, some assumptions

As with any good analysis, we need to start with some data and some assumptions. Fortunately for us, all of our data for this analysis of the flow of dollars within the 340B program is publicly sourced, so feel free to check our work, and thank those who make drug pricing data more available and accessible to the public.

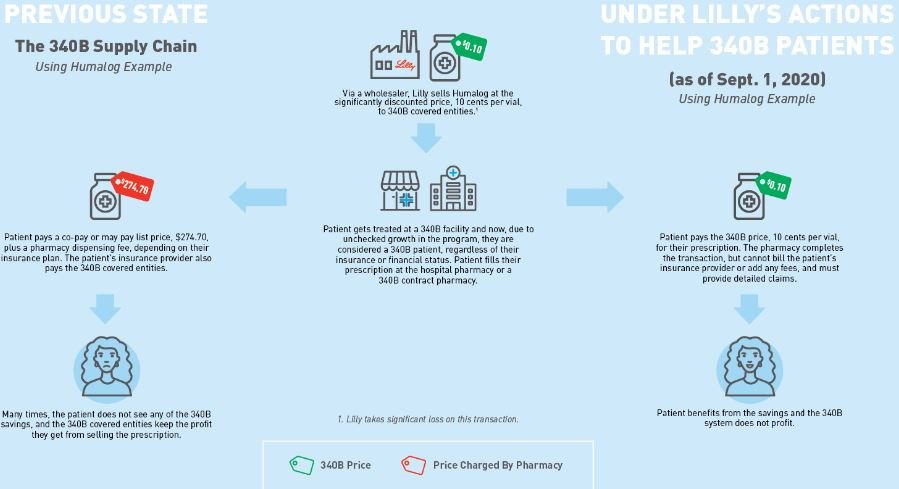

Our first assumption is to establish what the 340B price for insulin actually is. Fortunately for us, Eli Lilly told us the 340B price experience for their drug Humalog (as of Sept. 1, 2020). As can be seen below in Figure 2, Eli Lilly (who would know best) told us that the list price (i.e., wholesale acquisition cost, or WAC ) for insulin was $274.70 for a 10 mL vial. That same vial could be acquired through the 340B program for just $0.10 (an effective 100% discount).

Figure 2

Source: Eli Lilly & Co.

Now, this is the price of insulin as of September 2020 according to Lilly, but we believe it still holds valid through the end of 2023. There were no WAC list price changes for Humalog between September 2020 and 2023 (except of course for 76% decrease in WAC list price on 12/30/2023 – see our Brand Drug List Price Change Box Score). Because there were no list price changes, we think it’s reasonable to say this graphic is valid for the years of 2020 through 2023 (except for the 30th and 31st of December 2023)

Our next assumption is to establish what the average deductible amount is in the U.S. We need this value, because it establishes how much money a patient will have to pay directly for their healthcare products and services – in our case, the drug Humalog – before they get the benefit of their insurance copayment. Thanks to the Kaiser Family Foundation 2020 Employer Health Benefits Survey, we sourced this at $1,644 annually for 2020 (aligned to the date of Eli Lilly graphic in Figure 2).

Next we need to know what Humalog costs – what it costs for the insulin package to the health system, and what a patient pays to get that package after they’ve met their deductible. Fortunately, this was recently looked into through our team’s consulting work at 3 Axis Advisors, where using our recently-released World Insulin Price Comparison Map, we can see that the typical package cost for a vial of Humalog vial is $262 in the U.S., with a typical patient pay obligation of $25.72. The cost of the vial of pens reported there is at least in line with our own visualizations at 46brooklyn, assuming Medicaid managed care organizations are reasonable proxies to the commercial market, and also in line with other previous disclosures on price.

Now, the astute reader will note that $262 relative to the WAC list price of $274.70 is roughly a $10 underpayment to pharmacy. For the sake of making all of this easier, we’re going to go with the $274.70 number for both the reimbursement and acquisition cost number (but there is almost certainly a lesson there about underwater reimbursement on brand name drugs to pharmacies).

Lastly, we need to know what kind of rebates Humalog can generate. Lucky for us again, this information came to light at the start of 2021 via the U.S. Senate Finance Committee’s investigation into insulin costs, where it was stated, “Eli Lilly prepared widely divergent rebate bids within a few months of each other for Humulin and Humalog to a commercial health plan in Puerto Rico called SIS (22%), Cigna (45%-55% depending on formulary placement), a PBM in Puerto Rico called Abarca Health (up to 54%), and Optum’s Part D business (68%).”

Eli Lilly is the manufacturer of Humalog, and if the offer of rebates years ago was 68% to one of the largest PBMs (pre-2020), it seems reasonable to assume those rebates were available until the end of 2023 (when the WAC list price decreases occurred). And in fact, based on what we know about the general growth of rebates over time and recent reporting on Lantus’ net price (another insulin), we would believe that number to be a conservative estimate for the sake of this analysis (which is roughly aligned to what we know about insulin prices in 2020-2021). To be clear, the WAC for Humalog didn’t change from May 2017 to December 2023, and a 68% value of the wholesale acquisition cost (WAC) equals $186.80 today based on the $274.70 list price.

Crunching the numbers

With those assumptions out of the way, and our data points gathered, we can re-construct our Money from Sick People Model #1 that demonstrates how the cost for insulin is generally experienced by people with diabetes over the year, as well as the rebates that PBMs, rebate aggregators, and/or health plans are recognizing on each prescription of Humalog. Note, we are grouping PBMs, rebate aggregators, and health plans together in our model because it is largely irrelevant which entity is taking the money, and well, they’re increasingly the same organization. We construct this model again because we used a different insulin the first time around and just want to make sure the previous learnings from Lantus hold true for Humalog too (spoiler: they do).

Once this model is constructed, we can then compare the existing flow of money for Humalog relative to the 340B provider experience. From there, we analyze the impact of shifting the after-the-fact Humalog rebates from the health insurer/PBM/rebate aggregator to an upfront discount to a healthcare provider through the 340B program. And boy, does it change the Money from Sick People Model in meaningful ways.

Results

We start by reproducing the Money from Sick People experience for people getting insulin through their health insurance plan. As can be seen in Figure 3 below, although Humalog is a different insulin from our November 2021 rebate analysis (which used Lantus), the results are more or less the same (PBMs/insurance companies/rebate aggregators actually make money on people getting their insulin filled thanks to rebates).Health plans pay out (Column [C]) less than they collect in rebates (Column [F]); ergo money made (Column [G]).

Figure 3

Source: 46brooklyn Research

With this knowledge confirmed for Humalog, we can move forward with re-imagining how this all works when a 340B Covered Entity is dispensing the insulin to a person with insurance (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Source: 46brooklyn Research

In reviewing Figure 4, there are some things that may stand out. So let’s review each of the columns individually and why the math looks so much different from before.

Column [A] shows the 340B Covered Entity acquiring the drug at $0.10 per vial. This is sourced from the drug manufacturer (and is effectively 100% less than the normal cost to acquire insulin by non-340B pharmacies).

Column [B] shows the patient paying the full drug cost as if the claim wasn’t purchased at a super discount.

Not only is this the norm for most 340B-purchased drugs, but several states have enacted legislation that says that PBMs and health insurers cannot disparage 340B provider reimbursement (meaning that providers of 340B medicines cannot receive lower reimbursements than other market participants) even though we know they’re statutorily buying the drug at the lowest possible price.

Column [C] shows the health plan sharing in costs. PBMs and health plans share in drug costs in the manner that they normally do (not paying while the patient is in the deductible phase, and picking up their share relative to the patient’s copay/coinsurance after the deductible is reached).

Column [D] shows the 340B Covered Entities’ revenue off the sale of this medication. Charging full commercial rates to someone for something you bought for pennies, it turns out, is pretty lucrative.

Column [E] shows the margin made by the Covered Entity. Whereas before we assumed that pharmacy providers were not making any money on Humalog (even though evidence from Medicaid data suggests maybe they were losing money with average payments of $262 per vial), here again we’re seeing 340B Covered Entity pharmacy providers actually making a lot of money, because they’re not really paying anything material to acquire the drug.

Column [F] shows the PBM/health plan’s rebate, which for 340B claims is non-existent due to duplicate discount prohibitions.

Note that effectively all contracts between manufacturers and PBMs/insurers preclude claims acquired at the 340B price from paying a back-end rebate (if the manufacturer is providing a front-end discount to the provider, then the PBM can’t also harvest a back-end rebate from the manufacturer on the same claim), so we assume the insurer doesn’t get their money from sick people (the Covered Entity has captured it first). At a federal level, duplicate discounts between Medicaid rebates and 340B discounts are statutory (42 USC 256b(a)(5)(A)(i)), but in the private marketplace, the delta is generally a function of the contract. As way of proof, we provide a screen shot of the rebate guarantee language in the City of Mesa, Arizona’s contract with their PBM (which precludes rebates on 340B claims). This type of exemption language is industry standard, and if you find a PBM contract that doesn’t have this, please let us know.

Figure 5

Source: City of Mesa, Arizona

Column [G] shows the insurer’s net cost. As their cost is no longer reduced by rebates, the insurer doesn’t make money off the sick person anymore and pays effectively half the drug’s cost over the course of the year (i.e., real value with insurance related to this drug).

Column [H] shows the net cost of the drug (from the manufacturer’s perspective). They sell the drug for $0.10, and that is all they make per claim.

We should acknowledge that the above Figure 5 assumes that the Covered Entity has an in-house pharmacy who is dispensing the medication. That is not always the case. Most Covered Entities are hospitals, and not all hospitals have outpatient pharmacy services. However, the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) states that a Covered Entity can partner with an unlimited number of contract pharmacies to help Covered Entities stretch their scarce federal resources as a means of cultivating 340B spreads that go beyond the footprint of the Covered Entity.

For you Mandalorian buffs, you can think of contract pharmacies as bounty hunters – hired contractors meant to expand the reach of a search for wanted assets. And of course, with every successful 340B bounty collected by a contract pharmacy on behalf of a Covered Entity, the rewards can be quite handsome.

So what does that look like when a Covered Entity uses a contract pharmacy to dispense the medication (and not an in-house pharmacy)? And how does this relationship alter the financial picture of the transaction?

Well, we have at least one contract pharmacy-to-Covered Entity contract in the public domain. As can be seen below in Figure 6, the Jackson Memorial Hospital agreement presumes that a contract pharmacy who works with the Covered Entity will get paid a $65 dispensing fee for doing so and will get to keep a whopping 15% of the revenue from the prescription (note, this is the best 340B contract pharmacy revenue share we’ve ever seen based upon our channel checks, so this may over-estimate the typical experience at a contract pharmacy).

Figure 6

Source: Jackson Health System Public Health Trust Board of Trustees

If we modify the 340B model to include the contract pharmacy relationship (based on the above contract example), we get the following flow of money for our Money from Sick People model.

Figure 7

Source: 46brooklyn Research

If in looking at Figure 7 above compared to the previous one makes you ask the question, “Why would a Covered Entity give all this value ($3,296 Covered Entity Revenue compared to $2,021 Covered Entity Revenue) away to contract pharmacies?”, the answer is perhaps simpler than you think.

The mechanism of 340B Covered Entity to contract pharmacy actually functions retrospectively in most instances (i.e., a bounty hunt). Software companies like Macro Helix, Rx Strategies, Verity Solutions, and others analyze pharmacy claims activity at the end of each day for 340B claim eligibility. Claims that are found eligible at the contract pharmacy through these companies’ algorithms effectively transfer ownership of the claim from the contract pharmacy to the Covered Entity with the Covered Entity replacing the utilized inventory for the contract pharmacy. In other words, the contract pharmacy gets its inventory replenished (i.e., no loss of value) while at the same time getting paid a big fee for sharing the data with the Covered Entity for them to claim the prescription. If the prescription isn’t captured in the 340B web, then the provider stands to effectively make no money off of it (see Figure 3; pharmacy margin for brand insulin is effectively $0, especially considering the carrying costs) and the Covered Entity will make no revenue (the prescription isn’t associated with their activity). From the perspective of the Covered Entity, it is better to split the revenue than miss it entirely, which is why they are willing to pay big bucks for added 340B claims. (For those interested in more details on 340B contract pharmacy replenishment models, click here)

So, that was a parsec of information condensed into Jawa-sized stream of text, so let’s pause to unpack a bit.

First and foremost, rebates and statutory discounts tied to drug list prices are worth a lot of money. The examples above with 340B prices give us an appreciation for what “best price” practically means. Even getting a 68% rebate (i.e., commercial insulin rebate experience) can’t compare to purchasing the drug upfront for effectively 100% off the list price. The difference between a net price of $87 dollars for Humalog compared to $0.10 to Humalog is effectively an 800-fold decrease. To be clear, we know how impactful Medicaid’s “Best Price” rebate is thanks to analysis from the Medicaid and CHIP Payment Access Commission (MACPAC). From the MACPAC Trends in Medicaid Drug Spending and Rebates presented in October 2022, we see that brand drug claims in Medicaid are effectively reduced by 60% via rebates – the majority (67.2% of brand claims) of which are priced via their “Best Price.”

Figure 8

Source: Medicaid and CHIP Payment Access Commission (MACPAC)

Recall Medicaid rebates are effectively the upfront discount available to Covered Entities (the Medicaid discount is equal to the 340B ceiling price). Covered Entities are effectively buying brand drugs for $40 what others pay $100 for, according the figure above. That is a huge statutory advantage on drug costs; immense savings on what drugs cost to these groups.

To demonstrate, imagine two pharmacies across the street from one another. Each pharmacy has three patients who get a prescription of Humalog filled a month (say one vial each per person, per month). One pharmacy is getting Humalog at the 340B acquisition price, and the other is getting the normal pharmacy market acquisition cost. Over the course of the year, the non-340B pharmacy will need to invest $10,000 in inventory to stock the Humalog for their customers ($274 per vial * 3 vials per month [1 vial per patient per month] * 12 months in the year = $9,864). The 340B provider will need to invest less than $5 for the same amount of inventory for their customers ($0.10 per vial * 3 vials per month [1 vial per patient per month] * 12 months in the year = $3.60).

Arguably, that is what is meant by the phrase “340B Savings” (although the phrase is often used to lump both the upfront discount and the revenue made off selling products relative to this discount). A 340B Covered Entity needs to invest far less in their drug inventory costs than other providers, enabling them to use their money more efficiently. Consider that for a $10,000 investment, a 340B pharmacy could effectively open 2,000 locations that offered insulin compared to the one pharmacy location whose buying the normal way. That is a big competitive advantage alone. We emphasize the point because the savings alone are a valuable business commodity associated with lower carrying costs and major competitive advantages. The fact is that the goal of the 340B Covered Entity is to sell the drug at typical market rates (as evidenced by state legislative activity that seeks to enforce non-disparagement clauses against 340B providers) and they (Covered Entities) are positioned to use “340B Savings” to actually generate massive “340B Revenues.” So again, there is a significant economic disparity between Covered Entities vs. traditional non-340B pharmacies when it comes to the underlying investments needed to make in drug inventory for their respective businesses, but if you layer on payment which effectively makes one entity a lot of money, and the other very little, then the starting competitive advantages will compound into a race that a traditional pharmacy business cannot win.

To demonstrate, imagine both pharmacies receive $274 per prescription of Humalog they sell their customers, regardless of which business we shop at. Both businesses will make $9,864 per year for their three customers on Humalog ($274 per vial * 3 vials per month [1 vial per patient per month] * 12 months in the year = $9,864). However, the Covered Entities’ margin, relative to their drug acquisition cost, will be 99.9365% whereas the traditional non-340B pharmacies margin would be 0%. Which business would you invest in, if you could?

Now, Covered Entities like to point out that 340B savings/revenues are needed in order to “stretch scare federal resources as far as possible,” but given the amount of money in play, it seems worth questioning just how far these dollars stretch. Consider that for every one person with insurance who a Covered Entity charges the full price for, they can give away the drug for free to around 2,747 individuals. (In the figures above, the profit per prescription is $274.70 relative to a cost of $0.10; ergo, 2,747 people can be served off the profits of one prescription; when using a contract pharmacy, the ratio is ~1,600-to-1). The ratio of those in need for prescription drug support to those not in need is not thousands-to-one. At worst, we’ve seen studies which suggest 36% of Americans report that paying for prescription drugs has been difficult to somewhat difficult. And while that number is almost certainly too high, it doesn’t raise to the level of 2,747-to-1, which raises another point. The 340B revenues made off insulin are likely cross-subsidizing other services at these Covered Entities.

Covered Entities, such as local community hospitals, are absolutely heavily investing in their local community’s well-being. Many of the dollars harvested through 340B spreads are going to legitimate, needed care. But again, the flow of money in the 340B program highlights the broken role that money from sick people plays (whether it is a retrospective rebate or a massive upfront discount). In a rebate-driven system, the person producing the thing of value is not directly benefiting from it.

How much more affordable would customers of Covered Entities have found insulin to be if people got it at $0.10 a vial for the last decade or more? We recon, based upon the historic challenges with insulin affordability, a lot would have benefited from lower insulin costs. And to give a sense of scale, consider that more than half the hospitals in the country are 340B Covered Entities and that effectively half of all pharmacies (32K out of an estimated 66K) are 340B contract pharmacy locations. So it seems like there was ample opportunity for one or more of those involved in the 340B program (manufacturer, Covered Entity, contract pharmacy) to offer these savings to more patients than those that got them (and undoubtedly, some got free or reduced cost insulin that otherwise wouldn’t have). Which raises a bunch of questions regardless of what, or who, money from sick people actually benefits.

Baseless speculating on why we put up with sick patients overpaying for medicines to provide value to others

In reviewing what we feel we have learned as a society by examining insulin prices over the last 10+ years, we feel that it is clear that a lack of transparency regarding price has led to a pretty distorted drug pricing system. Whether the lack of transparency is the value of the rebate or the purchase discount, insulin truly exemplifies drug pricing dysfunction in that the people who need it are often paying more for it than makes sense. Consider, much as we did the first time when we reviewed Money from Sick People, that if the net price of Humalog (i.e., $87 plus a $10 dispensing fee) was recognized up-front (i.e., at the point-of-sale), the patient would pay less money than they did through their insurer (who captured rebate value the patient didn’t fully see).

Figure 9

Source: 46brooklyn Research

As before, in this model (Figure 9 above), the patient never reaches their annual deductible of $1,600 (though previously they reached it just halfway through the year), and the insurer/PBM actually recognizes no cost associated with insuring this drug. While one might typically assume that this would be a dream scenario for a health insurer – they collect a premium, provide zero dollars in patient support, while the patient pays the full freight for their medicine – the truth is that they would much prefer the rebate model shown in Figure 3, where the health insurer collects a premium, provides zero dollars in patient support, and collects $747.67 in additional profit to top it all off. Not a bad day at the office.

But what happens when we stir a little 340B into the transaction?

Figure 10

Source: 46brooklyn Research

Now consider, that if we perform the same theoretical shift with the 340B experience (where the patient pays the net cost up-front plus a $10 dispensing fee), we’ll see again that the patient pays far less for the drug over the course of the year (Figure 10); however, the provider (in this instance, a Covered Entity) makes far less money off this arrangement than the previous one. Again, this leaves the Covered Entity worse off than before, with less money to re-invest in other areas. However, that is exactly the point of money from sick people (rebates, statutory discounts, other terms) – the thing of value is used to benefit someone or something besides the person producing it. Which ultimately begs the question, why do we put up with this system?

Well, below we offer some perspective based on our years of studying drug prices and the policies that govern them. For the sake of clarity, we’re offering these perspectives from the point of view as if insulin was the only drug available in the marketplace. Obviously this is not the case, but insulin is the drug which offers us the greatest transparency into the inner workings of the rebate system; so we’re assuming that insulin is demonstrative of the issue at large (and therefore assume insulin is the only drug that matters for the purposes of these perspectives).

Drug manufacturer perspective

To start, one wonders why drug manufacturers endure such a system, where so much of the value of their medicines gets lost in the plumbing of the drug channel without the full value of their offered discounts being passed on to the end payer. Perhaps the quickest answer is that they don’t want to put up with it, as recognized by their recent lawsuits related to 340B contract pharmacies. However, those lawsuits not withstanding, they have an easy (albeit, impractical) way out of the 340B and rebate program. If drug manufacturers opted not to sign the National Drug Rebate Agreement (NDRA) with the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), then they do not have to offer Medicaid a rebate for their drugs, nor do they have to sell their drugs at 340B prices to Covered Entities (no obligation to sign the pharmaceutical pricing agreement (PPA) that governs 340B pricing). Problem solved, drug manufacturers make even more money, right?

While this approach is undoubtedly simple, it is likely not a practical business solution for most manufacturers. Consider that Medicaid enrollment was roughly 87 million people at the end of 2023 (roughly one quarter of the entire U.S. population). With those kind of numbers, it is very apparent that manufacturers would be missing out on large swath of the patient population by not signing a NDRA (to say nothing of the roughly half of all hospitals and pharmacies who may be less inclined to stock your drug if you’re not also participating in the 340B program via the PPA). At the same time, the rest of the market (i.e., commercial insurance) likely looks at the statutory discounts Medicaid is getting (did you see those MACPAC figures earlier?), and make demands for rebates for themselves as well.

However, we do not feel that is the entirely story either. If drug manufacturers are going to give rebates to everyone as a result of having to give them to Medicaid, why don’t they seek to equalize the rebate across the board? Said differently, inherent within the concept of Medicaid “best price” is the other side of the spectrum – the worst price – someone who is going to pay more (even after rebates or discounts) for the same drug. Other countries have more uniform drug pricing experiences through more rigid government programs or negotiations, so why don’t manufacturers advocate (rather than oppose) those programs here? We think the answer to that question is as simple as looking at their incentives, and we think we can do so with insulin, but first we need a few pieces of background information to make our point.

In 2021, Drug Channels Institute estimated the gross-to-net bubble in the United States to be worth $204 billion for brand-name drugs. At the same time, we know the size of 340B discounts purchased was $43.9 billion and Medicaid rebates were worth $42.5 billion. Proportionally, this means that roughly 42% of all brand-name discounts (i.e., $43.9 billion + $42.5 billion divided by the $204 billion total) were associated with these two programs alone, with the rest remaining for everyone else. If we conceptualize that in relation to Humalog prices, we think we gain valuable insights into why manufacturers might agree to this program in the first place. Diabetes is a common enough drug that it likely equally spreads its discounts across the market fairly proportionally to these overall figures.

Figure 11

Source: Eli Lilly & Co.

Recall from earlier that the net price for Humalog in 2021 was estimated at $87.90 for commercial insurance whereas Medicaid/340B got the drug for $0.10. Based upon these data points, we’d say that the effective net price for the entirety of the U.S. market in 2021 likely approximated $50.71 (44% of the market getting insulin for $0.10 [the amount of Medicaid and 340B influence], with the rest getting it for $87.90). This approximates what Eli Lilly told us their net insulin price per vial was in their 2019 Integrated Summary Report (which we feel at least semi-validates our methods since we’re using one rebate price for commercial when we know multiple exists).

Interestingly, this estimated net price for the U.S. market is the effective net price of Humalog as we would understand it from the Federal Supply Schedule (FSS), which listed Humalog’s price as $51.77. (as a reminder, FSS is supposed to be a proxy for best commercial net prices, further validation in our mind of where the market is). However, that price isn’t far from what we believe international prices for Humalog were at roughly the same time. A vial of Humalog was roughly $44 in Canada in 2020 or $55 in Germany in 2019.

But unlike those international programs where $50 is the “universal” price in their respective countries, the differentiation of price in the U.S. market gives the manufacturer “upside” opportunity. As times get better, less people are going to be enrolled in Medicaid; therefore, less people will get the “best price.” As less people get the best price, the upside for the manufacturer exists for the U.S. in ways that don’t occur in other markets. Consider what happens if we roll forward our proportionality to the numbers based upon 2022 data (leaving the Humalog net prices alone). In 2022, the total gross-to-net bubble from Drug Channels was estimated to be $300 billion; whereas the 340B program was estimated to be $54 billion and the Medicaid rebates were estimated to be $48.5 billion. Under this proportionality, Medicaid and the 340B program are now just 34% of the market (whereas previously they were 42%). Keeping our drug prices unchanged into 2022 means that now, the collective insulin net price is $57.90 (34% of the market at $0.10 net price; 66% of the market at $87.90 net price). As a consequence of “best price” program contraction, the net price for the manufacturer improved.

This, in our opinion, is a perspective often missing from the dialogue regarding net price motivations. In international markets, the only way for the manufacturer to improve their financial picture is though universal price improvement (i.e., all prices within the country’s market going up; a challenging feat). This was more or less confirmed in the appendix documents from Eli Lilly in the Senate Finance Committee’s insulin investigation (Figure 12):

Figure 12

Source: United States Senate Finance Committee

In the United States, the best price vs. worst price paradigm creates upside opportunity (with downside risk) that doesn’t exist elsewhere. And so, perhaps that is why the manufacturers endure such a paradigm as we have.

This in turn raises the question, why does the government put up with this system of haves and have nots?

Government perspective

The government has become a dominant payer in the healthcare space. Between the 80 million lives enrolled in Medicaid, the government is also helping to pay for the drugs of 66 million enrolled in Medicare. Collectively, these two programs represent roughly 40% of all U.S. lives (and therefore an approximate 40% of the healthcare market). However, they have very different drug price experiences. We know from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), no one gets a better drug price than Medicaid. Across the federal programs of Medicaid, the VA, Federal Supply Schedule, and Medicare, Medicaid is the best and Medicare is the worse (in terms of net drug price; see Figure 13):

Figure 13

Source: Congressional Budget Office (CBO)

In looking at the above, what Medicare spends $100 on, the Federal Supply Schedule will buy for $93, the VA will buy for $55, and Medicaid will buy for $35. Why put up with the differences? Well, the differences make it easier to finance the program most reliant on federal dollars (general revenues).

In Medicaid, patients generally do not pay premiums or generally share in any meaningful amount of drug costs (copayments generally capped at $8). Having best price protections for a subset of that federally-funded drug market makes the financing of those benefits far cheaper for the U.S. government than it might otherwise be. Again, consider a model where everyone in the U.S. got the net $50 cost – Medicaid would go from spending $0.10 per vial of Humalog to around $50. This would make servicing the benefit 500-fold more expensive. To be more specific (while doing back-of-the-napkin-style math), there were a total of 560,000 prescriptions for Humalog in Medicaid in 2021. If each of those prescriptions were $50 more expensive in the net, then added costs for Medicaid would have been $28 million annually. Ouch.

In Medicare, drug costs are shared via a variety of sources, including premiums paid by beneficiaries, direct subsidies provided by the Federal government, and retrospective price concessions (i.e., rebates) recognized as direct and indirect remuneration (DIR). Prescription drugs in Medicare are sourced through the private market, with rebates between Medicare and commercial being roughly equal (average Medicare rebate percentage of 28% compared to median commercial rebate of 22%; both in 2019).

However, we know that rebates generally make drugs more expensive for individuals (hence Money from Sick People). For example, the government acknowledged that pharmacy DIR was increasing patient drug costs in Medicare, therefore, it stands to reason that drug manufacturer DIR is also increasing patient drug costs (to the extent that a particular plan is not using it to lower patient cost share; not all plans are equal).

Again, some back-of-the-napkin math: In Medicare in 2021, there were 648,000 prescriptions for Humalog. If each of those prescriptions was $37 cheaper in the net ($88 to $51), Medicare would have saved $23.9 million. While a good chunk of change, recall our earlier number for Medicaid added costs was higher, meaning it’s a net loss to the government to equalize net drug costs across these two programs (to say nothing of the differences in how programs are actually financed and where the added costs would be recognized).

All of this is to say, Money from Sick People works in the interest of the government financing the bill. In the program where government dollars dominate payment (i.e., Medicaid without patient premiums or cost share), the “best price” rules determine drug costs. In the program where costs can be shifted onto patients, Medicare used Money from Sick People to do just that (money made on one person’s drug purchase can make another person’s healthcare services and/or insurance premiums cheaper).

And of course, remember, whenever someone gets the best price, everyone else gets a worse price. Government-mandated price concessions for their own growing programs creates upward pressure on the list prices that plan sponsors and patients are left to grapple with on their own. So when it comes to the government, it’s good to be the king.

Health plan perspective

We have already covered why health plans and PBMs prefer Money from Sick People. The ability to profit off someone’s drug therapy is pretty much unique to any form of insurance anywhere. Health plans generally use rebates to make their premiums look more competitive than they would otherwise be. Said differently, in a world without rebates, it’s highly likely that a stand-alone drug plan would be cheaper than a drug plan as they exist today; however, the cost of doctor and hospital insurance would likely be more (drug rebates can be used to make medical insurance seem more affordable – when it’s all rolled into one health plan).

While the ability to profit off drug rebates and create more attractive member premiums are obvious incentives for health plans to favor a rebate-driven system, their preferences may not appear so cut and dry when it comes to the 340B program, particularly given that health plans don’t get the rebates on those 340B-eligible claims (see contract exemptions).

We believe that the health plans and PBMs put up with the 340B program largely because they don’t notice the impact relative to their collective experience. Sure they would like to still get their rebates on claims dispensed through the 340B program (and maybe they do sometimes when duplicate discounts occur), but even assuming all programs are working perfectly, we can see why health plans might tolerate the 340B program. Again, we’ll use proportionality to demonstrate.

In 2021, Drug Channels (who also has some interesting perspectives on PBM profit opportunities in 304B) previously identified $204 billion in brand-name gross-to-net bubble spending – $43.9 billion related to 340B drug purchases and $42.5 billion related to Medicaid. If we remove the role of Medicaid from this, we would say that roughly 1-in-4 of the gross-to-net bubble dollars are captured by 340B ($43.9 billion out of $161.5 billion [$204 billion total minus $42.5 billion Medicaid]). In Figure 3 earlier, we showed that health plan costs are -$747.67 for Humalog annually per patient when they collect a rebate and +$1,493.88 when the 340B Covered Entity captures the discount. Well if 3 out of 4 times, a health plan can make $747.67, and 1 out of 4 times, a health plan loses $1,493.88, their net experience is still positive, ergo it is cheaper to have this model continue than to advocate for a model where all net prices are the same or 340B providers were not entitled to their discounts.

Again, the Money from Sick People perspective is creating more opportunities to win than lose, and so the system is preferred to the alternative. Recall again that if we move any of the discounts in the system up front – even if the health plan never incurs a cost due to the patient never reaching their deductible – the health plan is losing out on the money it is currently making (and therefore $0 is a higher cost to the plan).

Wholesaler perspective

Figure 15

Source: United States Senate Finance Committee

They can’t all be winners right? Surely if everyone else doing the “selling” of products (drug companies, insurance companies), then those next in the drug supply chain stream must be losing right? On its surface, the answer appears that yes, they may stand to lose from this system since, at least according to Eli Lilly’s own internal communications, they may be able to pass on higher costs to wholesalers if basically all the health plans prefer their drugs. (see email to the side from the Senate Finance insulin investigation). However, this is not likely the full picture in the wholesalers mind. To start, this email also signals that wholesalers are getting rebates / discounts themselves so maybe they like the system just fine. But then what role does 340B play for the wholesalers.

While it is true that wholesalers are generally obliged to sell the products to their customers at the 340B price (based upon the Covered Entity being on the list of eligible entities maintained by HRSA), which would undercut the margin they might otherwise sell the drug for (if they were a traditional pharmacy purchaser), wholesalers have found several ways to profit off the 340B program too. All the major wholesalers acknowledge the 340B programs within their 10k filings and many are able to earn additional revenue for their role in the 340B program. They do this through offering proprietary inventory management software and consulting services to help Covered Entities with program compliance. Prescription technology services are a growing portion of again, many of the large U.S. wholesalers. However, such segments are still small parts of the wholesaler operation relative to their traditional role of wholesaling drugs to customers (see McKesson reported revenues by segment below):

Figure 14

Source: McKesson 10-K (2023)

Therefore, the value of 340B to wholesalers might have less to do with selling the 340B technology services they offer, and more to do with the general pain of wholesaling traditional drugs to traditional customers. 340B Covered Entities are generally prohibited from obtaining covered outpatient drugs through a group purchasing organization (GPO). This may be the real value to wholesalers, considering that they generally acknowledge that GPOs are impediments to their profitability within those same 10k statements. As McKesson notes, their top 10 customers account for 68% of their sales and, “Many of our customers, including healthcare organizations, have consolidated or joined group purchasing organizations and have greater power to negotiate favorable prices. Consolidation by our customers, suppliers, and competitors might reduce the number of market participants and give the remaining enterprises greater bargaining power, which might lead to erosion in our profit margin.“ (our own emphasis added).

Wholesalers, it seems, may have an affinity 340B customers for this reason. Not only can they sell software and consulting services to them to manage the program (sales they can’t make to their traditional partners), but they can, at the same time, rest easier knowing 340B customers cannot participate in the GPOs, which may threaten their margins. Considering the concerns with pharmacy closures and the observations of 340B contract pharmacy growth, this sounds like it could be somewhat a win-win for the wholesalers.

However, it’s not all sunshine for wholesalers. As least, that seems to be what drugmakers are indicating. Well, drug manufacturers seem to think that the system may give themselves the opportunity to win more by charging pharmacies more. For example, in the Eli Lilly documents in the Senate Finance Committee’s insulin investigation, it was discussed by the Eli Lilly team that gaining formulary access via rebates may help reduce the 3.5% WAC fee they pay to drug wholesalers to inventory their drug (since wholesalers will face buy demand for their drug given the formulary access).

Pharmacy perspective

So if health plans, the government, wholesalers, and even the drug manufacturer can find wins via this system of best and worst prices, where does that leave pharmacies?

As we already observed with the wholesalers, pharmacies may face increase costs for drugs if wholesaler rebates for drugs drop off. However, we’re not sure that pharmacy universally loses via the rebate system either – so long as they get to play in the 340B space.

Recall that the 340B program and the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program are inherently linked. Also note that contract pharmacies make a lot of money dispensing brand-name drugs via the 340B program in comparison to their normal experience with traditional pharmacy claims. Based upon our Humalog model, pharmacies either make $0 for dispensing insulin (or maybe actually lose money) via traditional means compared to possibly making over $100 per prescription when positioned as a contract pharmacy through the 340B program.

In case the theme of these perspectives isn’t obvious at this point, as we move onto why pharmacies put up with this system, it is again a matter of opportunity cost relative to the status quo. The contract pharmacies who have the opportunity to make around $100 dollars in margin per prescription in 340B have the potential to off-set a lot of losses. If they were actually losing $10 per prescription of Humalog in normal circumstances, the $100 profit per prescription in 340B potentially offsets 10 of those prescriptions billed through traditional means.

The issue is a matter of potential disparity though. A pharmacy not plugged into the 340B system – whether as a covered entity or a contract pharmacy – is at a massive competitive disadvantage to its peers. When much of the 340B contract relationships are tied up in PBM-affiliated pharmacies or large pharmacy chains (who can command larger referral fees and spreads than their smaller and less favored competitors), the rest of the pharmacy market can be squeezed out pretty quickly. Said differently, a majority of pharmacy operating costs are tied up in the carrying costs of brand-name drugs – unless they aren’t because you’re getting brand-name drugs for close to free. Thus you will often find many pharmacists and pharmacies that do nothing but sing 340B’s praises, recognizing that it gives them rare access to the slice of “best prices” that other pharmacies may never experience. Whereas most of the traditional pharmacies – who are faced with the adverse economics associated with buying expensive brand drugs from wholesalers at bloated sticker prices and getting reimbursed at or below their acquisition costs by PBMs – are wondering why anyone would even want to dispense brand drugs (heck, some have already stopped stocking brands altogether), other more fortunately situated pharmacies are wondering how they kind get their hands on even more.

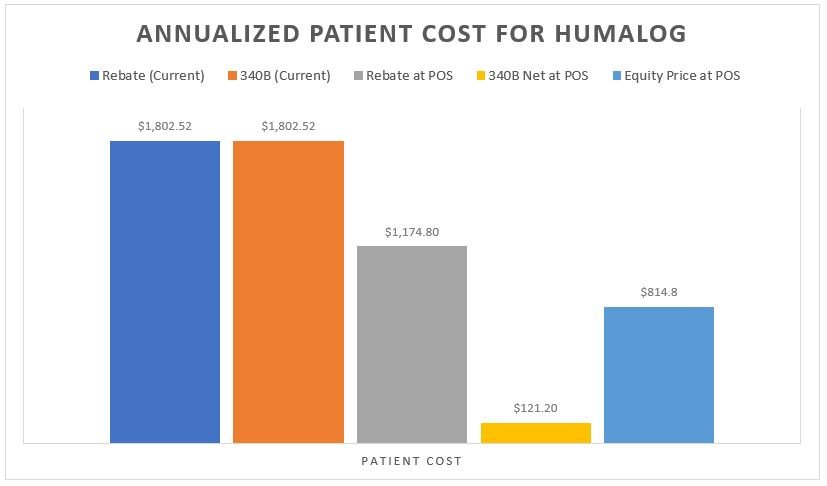

Patient perspective

As with with any analysis that deals with prescription drug rebates, last and least is always the patient. It is noteworthy that any model that would seek to recognize the net value of the prescription at the point-of-sale is an improvement for the patient. Whether it is the model where the insurer doesn’t take the rebate (i.e., $87 up front) or the Covered Entity doesn’t overcharge relative to their acquisition cost (i.e. $10.10 charge to the patient), patients would pay far less for their Humalog than they do today (see Figure 3 Patient Cost Column [B] for current experience relative to the same column in Figures 9 & 10). Similarly, if we imagined a world where everyone was getting access to the same net price (i.e., an equity-driven model where all payers are charged the net price of $51), the patients (collectively) are paying less (Figure 16 below).

Figure 16

Source: 46brooklyn Research

Putting all the various scenarios side-by-side from the patient’s perspective on Humalog shows perhaps why so many people were struggling with their insulin costs and rationing their insulin (despite low net costs available in the system today [either from the health insurance or the 340B Covered Entity perspective]).

Figure 17

Source: 46brooklyn Research, Column B from Figures 3, 4, 9, 10, & 16, Money From Sick People Part II

Ultimately, we feel Figure 17 speaks to the inherent misalignment of drug pricing today in ways that perhaps nothing else we’ve discussed today really can. Shouldn’t it bother us that the sick people who need the drug don’t directly recognize the full value of their drug’s rebate? Alternatively, should we be surprised that such a harmful system is increasingly used by an ever-more vertically integrated drug channel for their own gain? Especially given that for the largest vertically integrated players in the drug distribution channel, they can bear the fruits of the 340B program at multiple layers of their enterprise. Take a company like CVS Health (just for illustrative purposes). As an insurer (Aetna), a PBM (Caremark), and pharmacy (CVS), 340B can provide a cascade of profit opportunities to a publicly-traded company with none of the pesky obligations imposed on hospitals and other Covered Entities to provide care to those who otherwise can’t afford it.

Where are the market-based checks and balances when there is increasingly less market in competition with anyone but itself? Have you ever had an argument (think contract dispute) with yourself? Did you win the argument (with yourself)? Hmmm.

Final perspectives on Money from Sick People

Drug pricing is complex, subject to many potential different perspectives on the same set of facts. Given the heightened scrutiny of the 340B program (legislation, litigation, etc.), we understand that our delineation of winners and losers in such a hot-button space can be an easy path to enemy-generation. The end goal of 340B is noble, and there are many providers utilizing the program for incredible good. However, these facts should not detract from addressing the program’s deficiencies and contributions to American drug pricing absurdity.

Further, we believe it is prudent to ask the uncomfortable questions about the 340B program as designed today.

Given the program’s significant growth, are earned spreads being spent effectively?

Even if the Covered Entity is spending their spreads effectively, are the big cuts and referral fees earned by contract pharmacies appropriate and aligned with the intent of 340B “savings”?

Given that typical pharmacy claims yield much less margin than contract pharmacy commissions, is the economic inequity between regular pharmacies and contract pharmacies harming patient access and/or driving unnecessary pharmacy consolidation?

Understanding the inflationary pressure that Medicaid and 340B “best price” obligations places on drug manufacturer list price-setting decisions, is the rest of the market’s exposure to over-inflated list prices worth the bigger discounts paid through government programs?

Would passing the benefit of low priced medicines onto patients be of greater utility than earmarking spreads earned by providers for undercompensated services for patients?

Would the bloated list prices of medicines in the U.S. more closely reflect the prices seen internationally if we abandoned the current approach of funding government priorities, PBM profits, and insurance premiums through discounts achieved off those list prices?

To the extent that net prices are lower as prices raise faster than inflation, should we ask drugmakers to raise their prices higher as a means to generate more savings that can be used for further expansion of Medicaid, 340B, or other entitlement programs?

And while these questions feel targeted towards the 340B program, they could be easily tweaked to address similar issues with rebates as well (ergo, the issue with Money from Sick People writ large). And that we feel is the point.

We know that there is no panacea to the drug pricing dysfunction we see in the United States. If there were easy answers, there are enough smart people in Washington D.C. and across the country who have been studying drug pricing that any universal win-win-win scenarios would have risen to the top and been enacted (even with a government far more dysfunctional than the one we currently have). Rather, we offer today’s report knowing full well that Humalog is not universally representative of all drug pricing experiences in this country. Even now, we know that because of the price reductions on insulin, 340B Covered Entities who relied on insulin-related revenues are facing financial challenges in 2024 that they did not face in 2023 (a function of their reliance on Money from Sick People and a funding source that is tied to over-inflated drug prices). Rather, we used Humalog for today’s analysis because it just so happens to be the one of the few drugs with enough of the puzzle pieces on the board that we might actually start to grasp the complicated way our system seeks to rationalize drug prices while serving a bunch of often conflicting priorities.

Ultimately, that is the issue at the heart of the matter (as we see it). It is not clear to those of us at 46brooklyn what policymakers want drug pricing to actually accomplish in this country. Are we paying the highest rates in the world for drugs to develop ever more innovative and novel treatments? If so, then can we really complain when costs are high? Isn’t that the point of the investments we’re making? Alternatively, are we pricing drugs such that other healthcare services can be more affordable? Drug pricing data over time seems to suggest that no price is too high to pay for drugs, so long as it is associated with a juicy enough rebate. Said differently, we might as well let drug prices go to the moon, because then doctors and hospital visits can be free through cross-subsidizing the premium off-sets of those services relative to the drug’s costs (and we’ll likely need more of those services if we cannot afford drugs to maintain or improve our health). Do we care to ensure a robust network of pharmacy providers to access medicines and services? Are we trying to price drugs such that we can get access to the drugs we need when we need them? Well that almost certainly cannot be our goal when all of the levers of our system seem designed to disincentivize or otherwise financially punish the person who needs the drug that produces the rebate. How can we ever get better in such a system that pay-walls cures behind legal bribes for access?

And so we will continue to try and study drug prices, not because it is easy, but because it requires a great deal of perspective and dialogue.

And we welcome that dialogue. It is arguably long overdue.