MCuban v1

Setting the table

Prescription drug prices in the U.S. are not necessarily founded in a consistent, objective reality, but instead arise in different shapes and forms from a variety of places within our drug supply chain. They’re like healthcare’s version of sandworms. Undoubtedly, the price of a medication starts with a manufacturer (and the price they set), but it certainly doesn’t end there — nor can it be completely understood by just the manufacturer price point. A manufacturer principally sells their physical products (i.e., medications) to wholesalers, who themselves want to make money off the drug prices (applying some mark-up to them; often not equally to all drugs or all customers), as do pharmacy providers (they have costs beyond the acquisition cost of medications that they most recoup to maintain their business via the sale of drugs).

However, outside of the people directly responsible for the handling of the physical product, health insurers also look to make money of handling and managing prescription drug prices. Much like other members of the drug channel, many insurers are for-profit companies that have a financial motive to manage drug expenses in a way that produces a return as a means to sustain and grow their business. According to a recent FTC analysis released this week, roughly one in five of the national health expenditures (NHE) are handled by the largest healthcare organizations (health insurers + their affiliated PBMs, pharmacies, etc.).

As way of an example of the complexities by which our drug system operates, despite buying the overwhelming amount of physical medications, drug wholesalers (Cardinal Health, McKesson, Cencora) get less rebates from drug manufacturers than PBMs or health plans are able to obtain from manufacturers. In a practical sense, most businesses would expect that the person who buys the most product should get the biggest discounts, so why aren’t wholesalers getting them relative to their PBM peers? To give a more specific example, we know from the 2021 Senate Finance Committee historic insulin investigations that manufacturer rebates to PBMs for insulin could exceed 70% of the drug wholesale acquisition cost (WAC), but wholesalers were offered a 5% (or less) of WAC price concession.

So if the largest drug wholesalers purchase more inventory from manufacturers than PBMs, why on Earth would manufacturers be willing to surrender such massive discounts to PBMs despite their more meager purchasing clout versus wholesalers? To answer this question, we first need to understand why manufacturers offer these discounts in the first place, which is to secure market access (i.e. drive more sales).

The practice of rebating medicines is meant to facilitate a trade-off of value. PBMs decide which drugs to cover under insurance plans, along with additional powers to set patient cost sharing, prior authorization requirements, and a host of other tools that can be key factors what can temper a drug’s usage and sales. They are the ultimate kingmaker for medicines (especially for drugs that face any meaningful degree of competition). Wholesalers on the other hand sell drugs to pharmacies, who only purchase the medicines that are used by their patients (a function of their need and their ability to afford the medication). Since pharmacies don’t generally direct which drugs a patient takes (outside of brand-generic interchange and monitoring for drug appropriateness for patient/disease state), that means that their purchasing habits will reflect the end result of the intersection of physician prescribing decisions and PBM benefit and formulary design (which leads to the patient affordability and access). By extension, wholesalers’ sales will be reflective of that intersection (patient and their insurer - the pharmacy that stocked the drug) .

What this means is that the net negotiated price of a drug is essentially a sliding scale, where manufacturer discounts will be disparately doled out based largely on how much or how little a purchaser can ultimately influence their sales volume (patient and plans willingness to buy). Simply put, when it comes to the end price paid for a medication, results will vary based on size and more importantly, market share impact.

Which ultimately brings us to today’s report.

Much has been made about the vast pricing inconsistencies within drug purchasing. And while there are those that seek to deny how variable prices are, the simple truth is the facts are not on their side.

Undoubtedly, many find drug prices at the pharmacy counter affordable; how else would you explain the roughly five billion prescriptions filled in 2023? However, that number cannot tell us how many needed prescriptions went unfilled or delayed due to cost constraints. We know it happens, but it is hard to objectively quantify an observation of something that did not occur but otherwise would have. Perhaps one of the challenges in trying to understand drug affordability is the fact that despite more people having insurance now than ever before, we still face affordability challenges with medication access.

Since the end prices of a medicine are inconsistent and highly differentiated, we have a variety of drug pricing benchmarks in the U.S. that seek to quantify their many iterations. We’ve got a podcast series that goes over a bunch of them.

But even beyond those benchmarks, what often goes overlooked is the fact that drug prices arise, at least via insurance, in reference to the type of health plan we select. We have a variety of different types of insurance (HMOs, PPOs, EPOs, etc.). All of these plans are offered at potentially differing price points (as measured by the premium required to buy coverage) such that we undoubtedly buy more or less coverage depending upon how much money we pay upfront. Without going too far down this premium rabbit hole, we shouldn’t overlook that at the end of the day, the amount that we pay in premiums should factor into our perception of what drug prices are or are not. If you are paying more than $100 per month in coverage premiums, you’d expect to get much more affordable medicines at the pharmacy counter in exchange for that ongoing, upfront cost. Conversely, if you pay a $0 premium per month for Medicare prescription drug coverage, how much can you expect to cost-avoid at the pharmacy counter?

What we are investigating

While we think this concept of paying more in premiums in exchange for better out-of-pocket cost avoidance versus the opposite is pretty straightforward, in reality, it is far more ambiguous — especially when some drugs are so consistently associated with higher costs, regardless of which plan you select.

To investigate this phenomenon, we are deploying the thankfully transparent and downloadable Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug Company prices and running them up against the average Medicare Plan Cost and patient cost sharing amounts for the drugs that are offered by the Cuban company (while the Cuban program continues to add drugs to their portfolio, as a recent market entrant, they don’t have them all yet). Note, our team members (through work at 3 Axis Advisors) provide ongoing data analytics and consulting support to Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug Company, so while this analysis is not being performed on their behalf or request, it is a relevant conflict disclosure.

While many of the Medicare Part D plans had patient cost-sharing amounts that were less than what the Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drugs price, there were hundreds that didn’t (at least not for the majority of plans). Which begs the question, what kind of protection from inflated drug prices did our Medicare drug premiums actually buy? How is it that there are some drugs, regardless of which plan you select, that appear destined to pay an overly inflated cost relative to public data points like those provided by Cuban? In today’s analysis and report, we will unearth some of the distorted drug prices our system seems to have attached at the hip, regardless of what Medicare plan we enroll in (see Figure to the right, which will be explained in more detail later in the report).

Without the benefit of publicly available drug pricing insights like those provided by Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drugs, laypeople might believe that the high costs incurred for many medicines is reasonable (and expected). For a subset of medicines that will likely be familiar to loyal 46brooklyn readers, nearly every Medicare plan is signaling that these drugs cost a lot of money. However, because we have a price comparison to pharmacy (not a benchmark) that is a sustainable price for that business, these drugs beg the question — what does Mark Cuban know about pricing drugs that these Medicare plans can’t figure out? Or don’t want to figure out?

To help answer that question, we compiled a list of all the various drugs with each specific Medicare drug plan where Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drugs has an available price to compare. This list demonstrates when the Cuban pricing is cheaper than the Medicare plan sponsor’s pricing (whether measured at the gross price or the patient cost sharing amount) such that the public can better understand why these plans and their PBMs are acting the way they are, and more importantly, to potentially to help support patients in evaluating the myriad of Medicare drug coverage choices and trade-offs a little better (see figure to the side). After all, for some medicines, there could be thousands of dollars in difference (earlier figure) between what the prevailing Medicare plans are charging versus the prices offered at Mark Cuban’s still-young enterprise.

While this will provide a good window into some of the pricing anomalies that are impacting the Medicare marketplace, it is again, just a window. We are presently at work on a new dashboard that will contextualize all the publicly-available Medicare pricing information we can reasonably get our hands on, which we hope to release in the next month, so consider this a pre-game show. So if you’ve even wondered what drives drug pricing decision-making in Medicare, buckle up, because this report is our first step in a series that will dive into the abyss.

Drug benefit design in the news

Back in the later half of 2023, we had begun looking into Medicare drug pricing in new ways beyond our typical Part D Dashboard. Our focus at the time was largely in trying to understand what might happen with the much anticipated changes to pharmacy direct and indirect remuneration (DIR) going into effect in January 2024. As way of quick reminder, rather than Medicare plans and their PBMs paying pharmacies high at the point-of-sale just to collect money back from those pharmacies later via DIR (which increased patient cost sharing, among other things), the DIR policy change requires that pharmacies be paid the lowest rate at the point-of-sale (and maybe get some extra bonus money afterwards). The obligation to pay the lowest rate at the point-of-sale made us curious what the variability in drug pricing actually looked like (such that we might analyze what ‘lowest’ price may look like). Fortunately for us, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) makes available, on a quarterly basis, a public source of plan-level average monthly costs for formulary Part D drugs. Within this file, CMS publishes on a plan-by-plan basis what the average Medicare cost is for each prescription covered by the plan with the capability of determining anticipated patient cost sharing for each plan based upon whether the drug is dispensed at a preferred network pharmacy (if one exists) or a non-preferred network pharmacy.

What we found as we began to study this data was honestly difficult for us to initially wrap our heads around. We observed that the prices in Medicare for the same drug could be wildly different (like 100-fold difference from highest to lowest) based upon the various plans offering drug coverage benefits in Medicare. And while that alone was puzzling, imagine our surprise as we tried to bring in drug reference prices, which only further confounded us, as the highest prices were often much higher than even the highest drug reference price, but the lowest drug prices were similarly lower than the lowest observed reference price.

But that aside, what really shocked us was how variable drug prices could be within the same Medicare parent organization. Medicare calls the legal entity that owns a controlling interest in the contract organization a “parent organization,” and the distinction is important because of the complicated way by which Medicare plan bids become Medicare plans. Suffice it to say, a single parent organization can have many actual Medicare plans (like hundreds) which can result in one parent organization offering many different plans via Medicare. To give an example, UnitedHealth Group is a parent organization but it has contracts under names like United Health, but also AARP, Patients Choice, or others. Ultimately, the point we’re trying to raise here is that UnitedHealth Group as a parent organization has many different prices for the same drug amongst its different plans (which will become clearer later with actual examples; for both UnitedHealth and other Medicare parent organizations).

Through the various Medicare plans, Medicare enrollees are exposed, according to this quarterly pricing file, to many different potential drug prices for the same medication, even when dispensed at the same pharmacy. This means it matters very much which plans Medicare enrollees ultimately chose to enroll in.

https://www.wsj.com/health/healthcare/generic-drugs-should-be-cheap-but-insurers-are-charging-thousands-of-dollars-for-them-ef13d055

As we attempted to reconcile all these new learnings into cohesive thoughts, the results of our early analysis ultimately culminated in a fall report with the Wall Street Journal. In Generic Drugs Should Be Cheap, but Insurers Are Charging Thousands of Dollars for Them, the Journal’s analysis found that generic drug pricing in Medicare didn’t always align with the lowest cost pharmacy options (with Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drugs as a stand-in for low pharmacy cost options). As stated in the article, “Across a selection of 20 generic drugs carried by the Cuban pharmacy, Cigna’s prices were 27.4 times higher than Cuban’s on average for the 19 drugs for which data was available. CVS’s prices were 24.2 times higher on average for 17 drugs for which data was available. UnitedHealth’s prices were 3.5 times higher than Cuban’s on average for the 19 drugs with available data.“

And while figures like that above can be shocking (especially when you can see the range of prices for a given drug), the information presented in the article was already generally known through other means. Earlier in the year, the Journal had covered the results of a study that demonstrated Cuban’s pharmacy could have saved Medicare $3.6 billion over one year (roughly 2% of gross Medicare drug spending) with generic drug purchases at Cuban’s pharmacy versus what Medicare actually incurred. These results mirrored an even earlier study that showed Costco generic drug prices producing significant savings for Medicare.

What was gained from these earlier studies and the WSJ coverage of our initial analysis were greater details regarding individual drug price disparities (not just aggregate savings). The question asked at the time of these studies, and since, is how do these pharmacies (Cuban or Costco) price their drugs more competitively than some of the largest healthcare companies in the country? Said differently, what does a start-up like Mark Cuban know about drug prices that he can get them cheaper than the big three PBMs of CVS’ Caremark, Evernorth’s Express Scripts, or UnitedHealth Group’s OptumRx are able to secure for Medicare?

These questions are clearly of interest, as yet another study has sought to make comparisons between insured drug costs and Mark Cuban pricing. A recently released study found that for drugs carried by Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drugs, the amount that patients typically pay via cost sharing was generally cheaper than the price they would otherwise incur by simply paying the Cuban cash price. To be specific, the study found that across a sample of nearly 844 million prescription pharmacy claims for 124 different generic drugs Cuban offered, researchers observed that 11.8% (nearly 100 million claims) would have recognized lower out-of-pocket costs if they went with Cuban’s pharmacy than the cost sharing observed in data through their insurer. Putting their findings into a different perspective, nine out of ten people would appear likely to get cheaper drugs at the pharmacy counter with the use of their prescription drug insurance than the cash price offered by Cuban (i.e., the price without insurance).

However, what none of the studies reviewed thus far have adequately considered, is that prescription drug coverage cost money. Prescription drug plans are generally not free (and if they are, you get what you pay for — more on that later), but rather require a monthly premium to be paid (alongside deductibles or other hurdles) before the price at the pharmacy counter (i.e., the patient cost share) is actually reduced from what the pharmacy’s cash price would otherwise be. Said differently, Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug Company charges no membership fee to access their drugs (i.e., no prescription drug plan premium), so the analysis that nine out of ten prescriptions are more expensive than Cuban’s price is perhaps not completely contextualized given what we already know about some of the generic drug prices incurred through health insurance. Hence, today’s report seeks to analyze how benefit design decisions may influence the price of drugs.

Background on benefit design

The study of drug prices requires a great deal of context (as our readers are undoubtedly aware). And while we have generally focused our efforts to understand drug prices in relation to pharmacy pricing benchmarks (like Average Wholesale Price [AWP] or National Average Drug Acquisition Cost [NADAC]), we have dedicated no small amount of time to showing that there isn’t a direct link between those pricing benchmarks and the prices actually realized by payers (be they Medicare or Medicaid).

In 2022 (the latest year of which public data is readily available), Medicare spent $240 billion in gross drug spending (an estimated $164 billion in the net after accounting for the impact of DIR). These costs were incurred across roughly 53 million Medicare enrollees who elected to get prescription drug coverage in 2022. Medicare drug prices at the pharmacy counter arise not out of a set fee schedule, where Medicare would determine the price of the individual drug (like they do with Part B drugs and other services), but through the actions of private contractors for Medicare (the actions of the aforementioned parent organizations).

Across the nation, the average Medicare enrollee has close to 60 Medicare plans with drug coverage to select from (21 stand alone drug plans and 35 Medicare Advantage plans). If that sounds like a lot of choice, it undoubtedly is. By comparison, in 2023 (the latest data we’re aware of), 77% of employers offering health benefits offer only one type of health plan. When one considers that prior to becoming eligible to enroll in Medicare, the majority of us are likely getting health insurance through our employer, asking Medicare members to select from 60 plans can be daunting, as we are unlikely to have prior experience considering different benefit design choices. To go from essentially never navigating health insurance choices to go to Medicare, which one could argue provides too much choice, can be more than a daunting proposition, especially given all the intricacies.

And just like commercial insurance, Medicare prescription drug coverage is not free and comes with associated premium costs. According to the earlier mentioned study of commercial coverage, the average annual premium for employer-sponsored health insurance in 2023 was $8,435 for single coverage and $23,968 for family coverage. If that sounds like a lot more money than you pay, well the same survey says employees are generally on the hook for 17% of this cost (with employers covering the rest). These amounts for employer-sponsored health insurance are the amount for all healthcare coverage, which includes things like hospitals and doctor visits in addition to prescription drugs. In this way, the average cost is more readily compared to Medicare Advantage Plans (which also cover a variety of healthcare needs including doctors, hospitals and prescription drugs). As way of rough comparison, the average annual Medicare cost per enrollee was $15,727 (in 2022). Fortunately for our analysis today, Medicare also offers a stand-alone prescription drug plan (a rare occurrence elsewhere in the broader healthcare landscape). As a result, at least as it relates to Medicare, we have more or less a direct line of sight into the cost required to “buy” cheap drug prices at the point-of-sale. Said differently, in order to get the benefit of lower cost sharing on prescription drugs, there is a cost that has to be paid to get prescription drug insurance coverage, and Medicare gives us some of the best insights into what these costs look like.

Medicare Part D premium information

https://www.medpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/MedPAC_Payment_Basics_23_PartD_FINAL_SEC.pdf

The average total monthly Part D premium in 2024 is approximately $55.50 (which equates to $666 annually). That number was arrived via a highly regulated process that included Medicare seeking bids from potential contractors on the cost to provide prescription drug benefits. While we could all probably benefit from a better understanding of how the bid process works, it is not necessary for today’s exercise — we simply need to understand that it costs roughly $55.50 per month to enjoy the benefits of lower drug prices at the pharmacy counter with Medicare insurance. Nevertheless, for those interested in the details, we’re providing a link that explains how the Medicare bid process works, in addition to providing the following figure on the side as a rough overview of the process.

Analysis: Using Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drugs to contextualize Medicare plan drug prices

To begin our analysis, we first need to acknowledge that Medicare covers a lot of drugs. Designing Medicare coverage is a highly regulated affair, with CMS issuing rules regarding what a formulary can reasonably look like for a Medicare prescription drug plan. There are over 4,000 drugs available for coverage based upon the listed products in the Medicare Part D dashboard (which roughly reports medications on active ingredient). However, the reality is that a Medicare formulary represents tens of thousands of potential prescription drug products (at least on a NDC-basis). The variability in drug counts relative to NDC counts is a function of a given drug product potentially having multiple dosage forms and strengths (i.e., we might refer to the drug as Eliquis in the short-hand, but there are multiple strengths of Eliquis, like 2.5 mg tablets and 5 mg tablets, as well as six different NDCs [due to different packaging of these strengths]). Additionally, some drugs have multiple manufacturers for the same active ingredient, dosage form, and strength (i.e., the dozen or so manufacturers for metformin 500 mg tablets).

We prepared a new dashboard (below) which simply shows the variability in price across plans based upon a straightforward identification of the minimum Medicare plan reported price and the maximum Medicare plan reported price according to CMS. We roll these individual plans up to their respective parent organizations, but the dashboard enables the ability to click down to the individual contract level. This dashboard was effectively where we started with the Medicare quarterly file study.

To use the dashboard below, simply select which drug you want to view up top and observe the range of minimum prices in Medicare across the country as well as the range of maximum prices across the country. Each of the parent organization’s total number of unique prices is specified and if you click on the parent organization you can see the details of the underlying contracts as well.

As can be seen above, prices are highly variable for many drugs in many ways. And even variable within the same parent organization. And that variability requires closer scrutiny.

For the purposes of this report, we are not analyzing all of Medicare’s covered drugs, rather just those drugs where Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug Company has comparative pricing availability. Again, the goal in looking at this subset of only Cuban-available drugs is that we have a pharmacy provider in Mark Cuban (someone who directly buys drugs) self-identifying a sustainable payment rate for those drugs (by virtue of Mark Cuban having complete control of the formula with which he prices his products and services). We’re relying upon that as a measure of rationality and reasonableness for the price of each drug. It may be subject to concern, as not all pharmacies are effectively mail-order pharmacies, but it represents a good directional starting point.

Of the 4,000 or so drugs available for coverage, Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drugs has pricing for approximately a thousand of them (968 by our count; approximately 25% of all available drugs). These 968 drugs represent 2,500 NDCs, but that number is a little deceptive, as Cuban is covering mostly generic drugs and so his one NDC may represent a larger portion of the tens of thousands of drug products available. From a utilization standpoint, the Cuban products represent roughly 78% of the approximately 1.5 billion prescriptions filled in 2022.

Once we had identified the Cuban drugs, we were interested in analyzing Cuban drug costs against the plan-specific average prices reported in the quarterly Medicare formulary files. Note, when reporting prices to CMS, Medicare uses representative NDCs, which means we had to take efforts to match the Cuban products to the products listed in the quarterly file. However, because both Cuban and the Medicare files are reporting drugs on the basis of NDC, the ability to join in like-products was relatively straightforward. Once we were able to identify the selection of matching NDCs, we built a database that compared the average Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drugs price for a given product against the reported average gross price per Medicare plan, as well as the indicated patient cost sharing amount for the drug when dispensed at either a preferred network pharmacy (when available; not all plans have preferred networks) as well as the patient cost sharing when the drug was dispensed at a non-preferred pharmacy. More specifically, the current quarterly Medicare file is titled Q1 2024 and was compared against Cuban prices pulled down at the end of June 2024 (i.e., there may be some slight timing differences between reported events, but they should be minimal).

Once a pricing table was constructed for each Medicare contract with pricing (not all Medicare plans publish public information in the quarterly files; the specific exceptions are employer and Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly plans do not report into the database), we began comparing reported Medicare prices against Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drugs. There are more than 5,000 Medicare contracts with pricing for approximately 1,000 drugs, which means our ability to present our findings on a detailed basis was a challenging endeavor. Ultimately, we elected to evaluate pricing on a proportional basis for this analysis (but are currently working on a dashboard that will enable better individual drug analyses in the future).

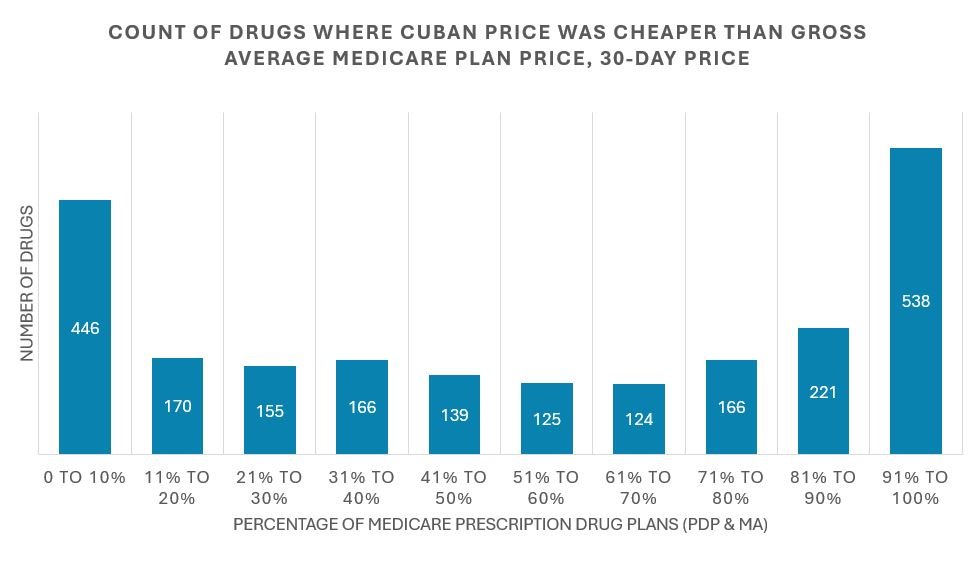

For today’s efforts, we are focused on counting how frequent the observed pricing behavior for Medicare plans was more or less costly than Mark Cuban’s price. To start, our first analysis was conducted from the perspective of the individual drug products Cuban has at his pharmacy. If the individual drug was one where no Medicare plans were averaging a gross price above the Cuban price, then we would identify and count that drug as one where 0% of plan sponsors’ gross spending was higher than Cuban’s price for that drug. Alternatively, if the drug was one where all plan sponsors were incurring an average gross cost higher than Cuban’s, we would record that as a product where 100% of plan sponsors were more expensive than Cuban. If eight out of every 10 plans had pricing cheaper than Cuban’s, we recorded it as a plan where Cuban was cheaper only 20% of the time. We graphed our results in the figure below. Note, as we indicated earlier, drug prices in the Medicare quarterly file are reported as both the price for a 30-day supply and the price for a 90-day supply, and those rates can be different within the same plan for the same drug. As a result, we have to present the information for each days’ supply separately.

The proper way to interpret the figure above is, as way of example, there were 446 drugs (out of the 2,500 that Cuban offered) where the Cuban price offered effectively no savings to Medicare (as the 446 value above is in the 0-to-10% range, meaning more than nine out of 10 plans already priced the drug at or below the Cuban price). Again, we think that this initial finding is perhaps not surprising when we consider some of the studies we reviewed at the start of this report. In order for it to be the case that only one out of 10 people would benefit from lower out-of-pocket costs with Mark Cuban, it would appear likely that the average cost for many of Cuban’s drugs would be cheaper within Medicare insurance than outside of it (i.e., purchased through Cuban directly, outside their plan). Conversely, there were 538 drugs (out of the 2,500 that Cuban offers) where nine or more out of every 10 plans were pricing the drug in such as way as to be more expensive than the Cuban price (which will warrant closer scrutiny later in this report).

If this seems a little complicated, we’re providing a link to the individual drug results here such that you can review how the above figure was generated on a more product-by-product basis. If you look at that workbook, you’ll see lisinopril 5 mg tablets as one where we do not expect Cuban to be of much savings. This make sense based upon what we generally know about lisinopril pricing in Medicare. If you look at the price of lisinopril back in 2022 (via the Part D Dashboard), the average cost per prescription in Medicare was roughly $8 (for roughly 80 pills). Cuban is seeking approximately $11 per lisinopril fill (for 90 pills) according to the CostPlusDrugs website ($6.80 in drug dispensing costs and $5 to ship the product). As a result, seeing lisinopril show up as a drug not likely to be associated with savings through Mark Cuban is an expected result (and represents one of our attempts to validate the data). Conversely, you’ll see other familiar drugs like imatinib mesylate and everolimus where Cuban is going to deliver savings relative to the prevailing Medicare plan rates.

While the above figure analyzes gross Medicare drug plan prices against Cuban prices, the following figures perform the same style of analysis solely for the anticipated patient cost sharing amounts to obtain the drugs (so just the patient out-of-pocket portion of the drug’s total tab). Note that cost sharing amounts are differentiated based upon whether the drug was to be dispensed at a preferred or non-preferred network pharmacy under the plan. As not all plans have preferred network pharmacies, the interpretation of these results can get a little tricky, as the denominator between the two comparisons is not the same. For example, we’re only comparing the proportion of drugs where Cuban is cheaper than the preferred cost sharing amount for the subset of plans with preferred pharmacy networks. Those plans will generally also have pricing for non-preferred networks (but not all non-preferred network pricing will have a corresponding preferred network price). We know — Medicare is confusing — but just know that those differences are not the focus of today’s report. But we have to explain them such that you understand why the below figures may not seem to exactly jive with one another.

Again, the figures above further reinforce the findings of the most recent study regarding Mark Cuban drug costs relative to solely the patient cost sharing amounts with insurance, but before we can start to unpack these findings further, let’s quickly show you the results for the 90-day pricing analysis. Again, as stated earlier, Medicare plans can report different unit prices for drugs on the basis of the drug being dispensed as a 30-day or 90-day supply (another way the same drug, at the same pharmacy, can have potentially different costs). For completeness sake, we’re showing the 90-day prices, and to save some space, we’re rolling the figures all together (as hopefully now they’re becoming a little more digestible).

So while the above figures perhaps represent a further directional validation of the findings of the earlier mentioned study (but not necessarily a proper contextualization of those findings), we are not quite done making comparisons of Medicare drug prices against Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drugs. You see, while the above represents the perspective of price for each drug, it doesn’t give us much of a sense of the value of the plan benefit within each contract we’re assessing. Meaning, sure, sometimes Cuban is more expensive than a majority of Part D plans, and sometimes he’s cheaper than a majority of plans, but what is a better sense the actual value proposition when considering both the costs of the medicines and the costs incurred through our premium dollars? <—BEN, I MADE SOME ADJUSTMENTS TO THIS, BUT I WANT TO BE SURE THIS IS CORRECTLY FRAMED

As a result, we wanted to also understand the inverse relationship — namely, were there certain plans where, for the majority of drugs offered by Cuban, their pricing was more than Cuban. While the above figures showed us what is happening on a drug basis across plans, this is trying to show us what is happening by a plan basis across the group of drugs. To do this, we looked at each Medicare plan, and for the drug prices that each plan has within the Cuban-available subset, we assessed across the collection of those Cuban drugs what proportion of plan prices were more or less expensive than Cuban. Now, for this analysis we had to not only break up the plans by their 30-day and 90-day prices, but we also had to analyze the prices across the stand-alone Prescription Drug Plans (PDPs) but also the Medicare Advantage Drug Plans (MA-PDP).

Ultimately, we were able to identify that yes, there are plans out there where four out of 10 times the typical cost of the drug for the plan sponsor was higher than the Mark Cuban price. This is significant considering the size, leverage, and sophistication of Part D plans relative to the upstart nature of Cost Plus Drugs. Which led us to look at the largest Medicare plans individually. They should have the greatest size, leverage, and sophistication, right?

As shown in the figure below, the variability in experience of drug prices for Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug products essentially mirrored the figures above. Some plans have very few drugs where Cuban represents a deal on the drug cost alone, whereas others may have roughly a third of products offered by Cuban where savings exists. And yes, we’re picking on plans within the top 6 that the FTC identified in their report.

Taken together, the above figures led us to do two additional investigations.

First, if you go back to the perspective of the individual drugs, there were a few stand-outs. Discussing dozens or hundreds of drugs in a short-ish report is difficult (hence why we provided links to the data and the dashboard of Medicare prices), so we selected those that seemed to represent drugs that were never likely to have reasonable prices in Medicare (at least as measured by Cuban’s price) across the various analyses thus far performed. In the figure below, we identify some of these drugs based upon what the data is showing us — and the results are honestly not surprising, considering that our prior research has revealed a host of pricing issues with the these frequent flyer upcharges.

In the table above, you can see that basically no Medicare plan is likely to offer a reasonable price on imatinib or abiraterone or a number of other drugs (refer to our previously linked per-drug Excel file for more examples). The average Medicare plan gross price for imatinib remains above $1,000 despite Cuban being willing to sell the product for $30. We imagine this is why Cuban prices have found a lot of fans in certain patient oncology support groups. Imagine if your blood cancer treatment cost $1,000 on your first month of treatment (because you went through your insurer) only to discover that someone else would have sold you the same drug for $30. We imagine you’d be pretty miffed. And yet, digging deeper into some of these drugs, we see that whether we look at the average price, the minimum price, or the maximum price across all the Medicare plans, no one seems to want to provide the above drugs at reasonable prices (at least as measured by Cuban).

To that end, we performed the second part of our analysis, which was to show the prices standardized between the largest parent organizations in Medicare on a minimum and maximum basis relative to the singular Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drugs price point.

And before we get accused of just cherry-picking negative examples, let’s return to some of the drugs where Cuban didn’t seem of value. Recall that we earlier identified lisinopril 5 mg as a drug where no plans were likely to be charging more for the drug than Cuban. Well, it turns out that may not be entirely true — rather our perception of the issue appears to have been clouded by effectively how many decimal places we carried out in our observation.

When we looked at minimum and maximum average price per Medicare plan within the quarterly files, imagine our surprise when we found maximum lisinopril prices above the Cuban price. We had previously identified no plans having an out of whack lisinopril price, so how come the details were disagreeing with us? Said differently, how is a plan out there pricing lisinopril 5 mg in excess of $20 per month when the data showed 100% of plans were pricing it below $12?

The answer goes back to all the plan choices Medicare offers. Across the nation, there are more than 5,000 prescription drug plan options, which means that in order for us to observe the drug as having irregular plan pricing, it needs to reach a threshold where at least 50 plans or more have the product higher than Cuban’s price for it to show up as just 1% of plans having a higher price than Cuban. There appear to be less than 50 plans that would charge high lisinopril prices, and yet, there are plans that may try to have you incur a gross cost above $20.

This example is illuminating in so many ways and brings us back to our earlier discussion on premiums. It shows that while yes, some drugs can really take an individual to the cleaners in regards to excess charges, and others can accrue value across a thousand cuts. Furthermore, it is demonstrative how one price and become many price with various perceptions of drug cost savings.

One of the plans that has high average lisinopril prices listed by Medicare (at least based upon the average gross cost reported in the quarterly Medicare files) is the 2024 AARP Medicare Rx Walgreens from UHC (PDP). This plan has a monthly premium of approximately $80. Now fortunately, lisinopril is a preferred medication within that plan with a flat $2 copay, but undoubtedly part of the reason why the copay is so low is because the premium is so high. Which brings us back to the whole reason we started this report.

When we consider patient drug cost sharing with insurance, we should consider the investment of premium dollars that are producing the end cost sharing amount. When a simple drug like lisinopril can have hundreds of different prices just within Medicare plan offerings (being as cheap as $0.23 — less than a stick of gum — to more than $20), we do no one any favors to say, “the value of your insurance is clearly of benefit” when we don’t adequately contextualize that the $2 copay required an $80 premium (hence why perhaps prior reports focused on gross prices; to no discredit to patient cost sharing).

The reality is drug prices are not always experienced in consistent, rational ways. We know from the Rutledge v PCMA decision that PBMs do not price drugs (at least generic drugs) in relation to their acquisition costs. But the disparate and opaque PBM prices leaves us grasping at straws for what they’re actually doing with drug prices.

What even is the price of a drug?

If you’ve made it this far into the report, you’re likely asking what the big takeaways are. Is it that Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drugs is saving money on drugs compared to Medicare plans? Is it that he isn’t saving money? While these are good insights to glean, we’d like to draw your attention to what we feel is perhaps the most stunning data in this study. We think it starts with a simple realization that drug prices in Medicare are variable (by factors of up to 100x from min to max). If you go digging in the dashboard, you’ll see there are contracts out there that have just one price per a given drug, but those plans are small (and the exception). Most plans have dozens of prices and most of the Parent Organizations (particularly the largest) have hundreds of prices. That is concerning given what we know about generic drug prices.

We know that the origin of generic drug prices are not manufacturer list prices, but PBM MAC lists. PBM MAC lists are the only way you can get hundreds of different prices for the same drug (not drug reference price will give you that kind of variability). Furthermore, we know MAC lists are the predominant way that generic drug prices arise at the pharmacy counter. However, what is claimed about MAC pricing doesn’t seem to match what our data is showing us. According to industry, “MAC pricing is designed to promote competitive pricing for pharmacies as an incentive for them to purchase less costly generic drugs available in the market, regardless of the manufacturer’s list price.”

If you look at the prices in the figures directly above for lisinopril, imatinib, abirariterone, and tetrabinazine, you can see that there are pharmacies out there willing to set one drug price across the country, and yet, PBMs are not setting one price, and often are setting prices with 100-fold different from min to maximum. What possible rationale incentive can pharmacy providers discern from such pricing? We are unsure what market, pharmacy not withstanding, would be able to discern what product to purchase for the lowest price when the experience is potentially 100-fold different monthly.

The facts are that PBMs have assumed the role of drug pricing experts within our drug supply chain. Whether intentional or not, it is increasingly clear that the primary value proposition of the PBM to the drug supply chain is as the entity that knows what a drug’s price is. They alone are the sole entity that can see the rebates offered by drug manufacturers, the prices pharmacy providers are willing to take via their network guarantees (both at the point-of-sale and after reconciliation), and the cost health plans are willing to incur to secure prescription drug benefits for their covered lives.

And yet, one wonders how organizations so dedicated to lowering drug costs (PBMs claim to be the only organization working to lower costs) can be creating such disparities in drug pricing. As their trade group PCMA has professed, “In Medicare Part D, pharmacy benefit managers, PBMs, negotiate directly with drug manufacturers and pharmacies to provide beneficiaries with the lowest possible prescription drug costs and the highest quality pharmacy experience.” One wonders how the Medicare Parent Organizations, with insights into all their contracts various pharmacy prices, can square such statements with the data. How did they decide who gets the high end price - and how is that price aligned with securing the lowest possible drug cost? How does setting such variable costs square with incentivizing pharmacies to purchase prices more competitively?

XXXX.