Treating the drug pricing perception problem

In our recent review of the drug pricing changes that occurred in the month of June, we did a quick sidebar into an intravenous hypertension medication called Cardene. After releasing that report, we got a lot of feedback from a variety of stakeholders (manufacturers, hospital pharmacists, wholesalers, patient advocacy groups), and one of our charts got featured in STAT’s essential Health Care Inc newsletter. To say we were surprised doesn’t really capture our sentiment, as we may occasionally get an individual or two that wants to talk to us about a specific item in one of our monthly updates; so it happens that a drug is of interest, but the discussion on Cardene was the first drug in awhile that brought so many different people to our 46brooklyn inbox. Given the interest, we decided that we should probably do more “Cardene-style” analyses on future updates.

So over the last few weeks, we were looking at the drugs that took price increases in July for one that we could do a deeper dive into, which resulted in us gravitating towards Opdivo (nivolumab). Opdivo is a medication used to treat adults with certain types of cancer and during July, the drug had a 2% price increase. We selected Opdivo not because it was the biggest or even the least brand price change (like Cardene was for June), but because it reminded us of the origins of 46brooklyn.

We began 46brooklyn Research with a report titled “The cancerous design of the US drug pricing system“ (which coincidentally was released in July 2018) that exmained some of the pricing distortions and anomalies with another popular oncology medication called Gleevec. Opdivo, also being a cancer medication that, unlike Gleevec, is infused over time by a healthcare professional (generally in an outpatient setting) was the perfect drug to single out for a deeper dive. The problem was that as we dove deeper, we quickly realized that this Opdivo story – centered on the all-over-the map pricing yielded between hospitals and health plans – needed to stand on its own rather than be embedded within our monthly update report.

As you will see, Opdvio reminds us that a drug’s price ≠ a drug’s cost, and perhaps that is the origin of the cancer of our drug supply chain that we have not been able to excise despite first putting a spotlight on the problem over six years ago.

Shopping for drug therapy

Although cancer is certainly a terrifying, life-threatening diagnosis, it isn’t one that typically requires emergent (i.e., immediate) treatment (note: this is a generality and not medical advice, listen to your doctor if you have cancer). So while you will often want to begin treatment reasonably quickly, medications like Opdivo can represent good ‘shopping’ opportunities for patients who reside in areas with hospital/clinic competition that might give them access to lower prices through the aforementioned competition. Unless of course we believe that drug manufacturers, and drug manufacturers alone, set the realities of drug prices – in which case, shopping wouldn’t be necessary; you’re price will have already been determined by them.

However, we know that there is more that goes into the cost we pay for medicines than a simply manufacturer list price. And we’re not alone. Apparently, there are folks in the federal government that agree too, as evidenced by previously implemented policy – the Hospital Price Transparency rule – which requires hospitals to report in the public domain a few price points for their services. Specifically, since the regulation went into effect in 2021, hospitals must publish the following in the public domain (as a machine-readable file and a consumer friendly online shoppable service tool):

Gross Charge: The charge for an item or service listed in the hospital’s chargemaster, without any discounts

Discounted Cash Price: The charge for an item or service paid in cash (i.e., without insurance)

Negotiated Charge: The charge between the hospital and a third-party payer

We view the Hospital Price Transparency rule as an acknowledgement that the costs we incur for a drug is more than just what the manufacturer says the price is. Said differently, there would be no value in these files – nor in the ability to shop – if we would incur the same cost provider-to-provider simply because the manufacturer had published one universal and prevailing drug price.

Can I get a price check on Opdivo?

Billing for hospital services is complicated. So much so that it is common for drug manufacturers to publish guides for hospital coders / billers on how to bill for their medication. Opdivo is one medication with such a guide (we will revisit that in a moment).

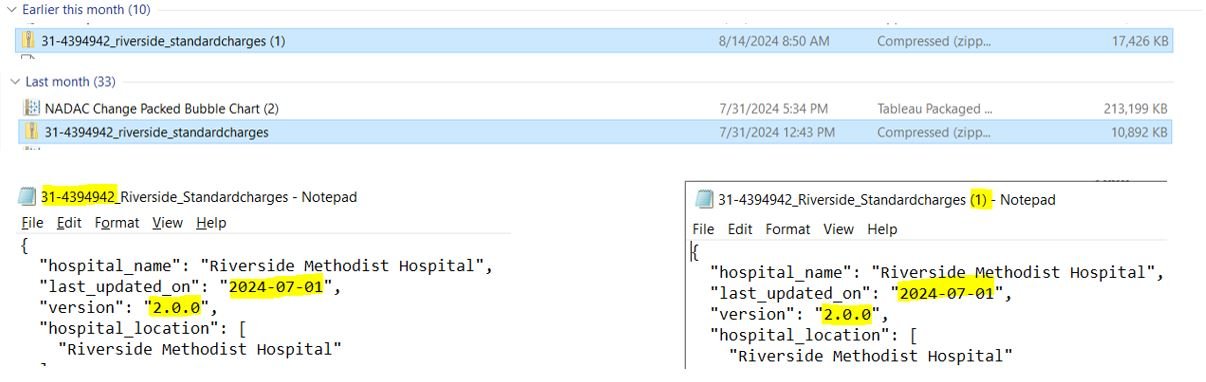

Since we published our look at price differentials for Cardene IV at OhioHealth Riverside Methodist Hospital in central Ohio (selected entirely due to it being the closest large hospital to our analysts) in our June report, we noticed that when we went to the same data source at the time we pulled prices for July during our look at Opdivo, OhioHealth had appeared to have updated their chargemaster. If you look at our download folder below in Figure 1, you will see that the compressed file size of the chargemaster had almost doubled (despite the files themselves having the same name and version number – which leads to the question of what good is a version number if you’re not going to update it as updates are made?).

Figure 1

Source: OhioHealth Riverside Methodist Hospital, 46brooklyn Research

If we hadn’t saved the file or otherwise backed up our work, we likely wouldn’t have recognized the update, as historical files don’t appear to be stored on the OhioHealth website (nor does it seem to be the norm for other hospitals). Upon our high level review of the update, it isn’t immediately obvious what has changed between the versions of the files (despite the change in size), but for the removal of doubt, we’re using the file as downloaded on 8/14/24 (though still stated to last be updated on 7/1/2024 and version 2.0.0). Since playing around with hospital chargemasters is a relatively newer hobby for us, we aren’t entirely sure of what is considered normal operating procedures with these types of files; so if there are folks who want to offer us any insights, or perhaps someone over at Riverside can explain what’s going on, please drop us a line, as we’re interested in learning what we may have missed.

Moving on, with our data source identified, we return to the digital reference guide to Reimbursement & Coding for OPDIVO® (nivolumab) from Bristol Myers Squibb (Figure 2), where we can see that Opdivo is billed under Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) code J9299, generally alongside Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code 96413 (a code used for the time it takes to infuse the medication in the hospital/clinic). As a reminder, this is not a medication that is self-administered, but will be prepared for provider administration for the patient, and then the patient will wait at the hospital/clinic while the medication is infused via an IV for 30 minutes or more.

Figure 2

Source: BMS Billing Guide for Opdivo and Yervoy

Having this guidance from the manufacturer will be helpful for our exercise today, as we can use it to identify what charges for Opdivo might be used for patients who receive this service at a hospital like Riverside. To start a potential shopping / billing exercise, we should recognize that OhioHealth (inclusive of Riverside Methodist Hospital) offers an online tool to estimate patient costs; however, J9299, CPT 96413, nor any combination we could think of (i.e., drug name, generic name of drug, listed description from billing guide, etc.) got us to the point where we could get an estimated price from the tool for Opdivo therapy services (see gallery below; screen shots as of August 28, 2024).

Again, this shopping tool exists as part of prior policy that required it to exist, but the rules do not require hospitals to have every service available on the online tool. Said differently, it is not necessarily a sign of anything being technically wrong that we couldn’t find what we were looking for. However, it does mean there could be value in beefing up the requirements if shopping for expensive cancer infusions aren’t showing up in these tools (at least in our opinion). It also means we will have to do a little more work in order to get an estimated price from the information Riverside Methodist is putting out in the public domain.

But before we get to Opdivo specifically, we did have a little success with just the word “infusion”, so here is what it might have looked like if we were successful (in the interest of full disclosure; as you can see, the CPT code for the infusion that was found is not the likely infusion code that will be used; see gallery below; screen shots as of August 28, 2024):

So while the online tool wasn’t a success for the the purposes of our Opdivo pricing hunt, we were not necessarily discouraged. We know that the prices are out there, due to prior policy work, and fortunately we are not intimidated by large data files with complex data structures (at least what we think most people might say is complicated). All this is to say that while the average person may not be able to access the data contained within a raw hospital chargemaster file, we could and so we relied upon the Riverside Chargemaster file to work out a pricing estimate for Opdivo from Riverside Methodist Hospital. Note that there is not a central repository for chargemasters (in a city, state, or national level). This means that it can take a good deal of legwork to find them. We bring this up not necessarily because it was hard to find Riverside’s Chargemaster, but because we have heard from others that finding chargemaster files can be as much work as interpreting the files (which to us, suggest that these files may not be as transparent as some may think – what good is a “transparent” price if you can’t find it?).

Talk is cheap. Show me the code.

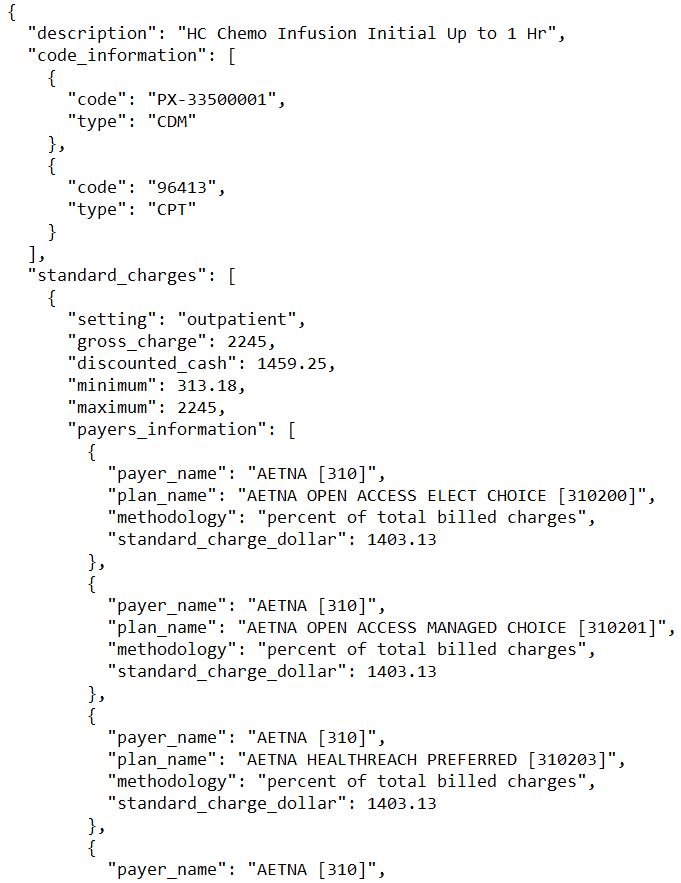

To properly use the Riverside Chargemaster file to get an estimated Opdvio charge, we need to first recognize that while there is only a listing for CPT 96413 within Riverside’s file, there are five different J9299 products on the Riverside Chargemaster; each with slightly different prices (gallery below).

Now, different prices for different strengths and amounts may not necessarily be problematic. For example, the 40 mg strength has six-times less active ingredient than the 240 mg strength, which is to say, if we were pricing this like smart phone data storage, we may see different prices for the different strengths or values as a function of the different amounts of drug within each product (i.e. you pay higher dollars for greater amounts).

However, when we work the charges of each Opdivo product within the Riverside Chargemaster down to a unit level (specifically the HCPCS billing unit), we see that unit prices for the various Opdivo charges at Riverside are different. The design of HCPCS codes is supposed to standardize medical billing, and while there are quite literally books written on understanding HCPCS codes, for our purposes today, we just need to understand that when we use HCPCS J9299, the standards suggest that we’re expecting to bill 1 mg of drug for each 1 HCPCS unit we bill. And so when we see these products having different per-unit prices, and cannot explain those differences after working down the price to the billing unit level, what we’re seeing is that there doesn’t actually appear to be a standard billing amount for the drug by Riverside. Below, we attempt to show the math for what we’re talking about here – pay attention to the HCPCS Unit Price columns to right to see the variability we’re trying to point out (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Source: OhioHealth Riverside Methodist Hospital Chargemaster, 46brooklyn Research

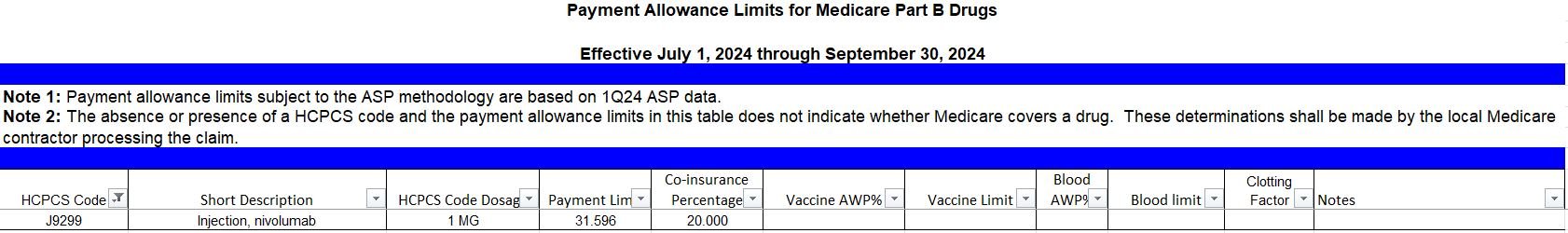

If you’re not following the math, that is OK; we understand this is a new world for most of our readers. What we’re showing in Figure 3 is that while we had expectations that unit prices at Minimum, Maximum, or Cash Discount would be the same whether the version billed is the 40 mg / 4 mL Opdivo product or the 100 mg / 10 mL product, what we found is that the prices are different (columns [I] through [L]). To be clear, the reason we had this expectation is not because the manufacturer has set the same WAC unit price for the drug regardless of strength (which they did, just the WAC is billed at the mL level rather than the mg level), but because the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) actually have a list of published prices at the HCPCS level, and each of those prices is uniformed for drugs across the various strengths. To be specific, CMS’ HCPCS billing for Part B (i.e., Traditional Medicare) states that there is no difference in the Average Sales Price (ASP) for J9299 (i.e., the same drug as what we’re looking at in Figure 3); meaning the HCPCS unit price would be the same were CMS providing reimbursement regardless of which strength / volume we used (see Figure 4). Said differently, from the perspective of CMS, it doesn’t matter which Opdivo product (i.e., which NDC) a hospital like Riverside Methodist would bill for; they will pay the same unit price regardless. However, the Riverside Chargemaster suggest that standard approach to billing does not exist (i.e., what you are charged can be a function of which Opdivo product you’re billed, not simply that you got Opdivo).

Figure 4

Source: CMS ASP Pricing Files, 46brooklyn Research

Note that the ASP from CMS is a statutorily defined price that is calculated by CMS based upon information submitted by the drug manufacturer. So while not directly a manufacturer price point (like Wholesale Acquisition Cost [WAC]), it is effectively a manufacturer-derived price – particularly for brands – as it would not exist but for the information submitted by the manufacturer. And for each brand product that CMS publishes an ASP price for, there is only one price per brand product (i.e., although several strengths of Opdivo [nivolumab] exist, each has the same HCPCS unit ASP price from CMS, and the only way to get an Opdivo product is from Bristol Myers Squibb).

The fact that the products have varied prices at Riverside Methodist and one price with CMS is perhaps the first signal that the price we may end up paying for our Opdivo therapy may be different for reasons beyond what we may expect. For example, Figure 3 is telling us that price may be different based solely on the different product selected to be dispensed by the provider (even if an equivalent dose from a different product would have gotten the same price). So even if we price out our Opdivo therapy (as we’re about to attempt), then we may still end up paying more than expected simply because the most economical product wasn’t selected to be dispensed when we got our treatment.

Healthcare Cost = Drug Cost + Service Cost (maybe?)

Before we can get a price estimate, we need to also address the time it is going to take to get the infusion (i.e., CPT 96413 as recommended by the manufacturer’s billing guide). Remember Opdivo is not a self-administered drug, and when patients go to get it, they’re actually going to have to sit and wait while the medication is slowly infused via IV. As it relates to the CPT code 96413 – which is the billing code for the infusion of up to one hour – we should note that the listed charges at Riverside Methodist range from as little as $313.8 to as high as $2,245 (Discounted Cash price is reported to be $1,459.25). This four-fold difference in the cost to “sit in the chair” while the drug is infused (based upon which payer negotiated the payment rate) is interesting, as one would not expect that there is a 4x difference in the cost to the hospital to manage people at what is effectively a seat in an office room (to be fair, the chair we’re sitting in is likely surrounded by a bunch of advanced equipment to protect our health; and so it is a valuable chair to sit in for sure). While we may not perceive a worthy justification, there very well could be rational reasons that we are unaware of for why a four-fold difference in price exists, but we do know that approximately 44% of Americans cannot afford a $1,000 (or more) unexpected expense. Therefore, we cannot help but feel this range of pricing represents something that someone may be able to afford ($313) to something they may not ($2,245).

With all that background out of the way, let us estimate a treatment cost with Opdivo at Riverside Methodist Hospital in Columbus, Ohio. To hopefully make this as easy as possible to follow, we’re going to presume that we need treatment for “Completely Resected Stage IIB Melanoma“, which according to the manufacturer billing guide means we may anticipate getting Opdivo monotherapy at a dose of 480 mg infused over 30 minutes every four weeks (i.e., monthly) for up to one year (see page 19 of the BMS billing guide). Note the 240 mg dose is administered every two weeks, so we get the same total amount of drug per month regardless of which strength is chosen. For this analysis, we chose the strength that requires just one visit per month (and therefore only incur one infusion cost) as opposed to two. Based upon our assumed diagnosis and assumed dosing regimen, we will need 480 mg of Opdivo billed (480 HCPCS Units of J9299, or 2 of the 240mg/24 mL products; or 4.8 of the 100mg/10 mL; or 12 of the 40mg/4 mL) and 1 CPT 96413 billed each month. As can be seen below, the range of potential costs we may face for this medication are quite varied (Figure 5).

Figure 5

Source: OhioHealth Riverside Methodist Hospital Chargemaster, 46brooklyn Research

In looking at Figure 5, the biggest anticipated cost driver is obviously going to be the drug cost. While again, there is a four-fold difference in infusion cost per the Riverside Chargemaster (and an almost $1,700 price difference), the drug cost can be as low as $13K or as high as around $63k (also an almost four-fold difference, but a much higher dollar amount). Because in the grand scheme of things, that infusion cost is a small portion of the overall cost estimate (regardless of which end of the drug price spectrum we’re on) and because the infusion costs distract a bit from the drug cost (hey, we’re drug pricing guys), we’re going to drop the infusion cost so that we can compare the drug cost of the hospital’s chargemaster against CMS’ traditional Part B cost for the drug (via the ASP price – note that CMS reimburses at ASP + 6%, so we’re increasing the ASP price by 6% to arrive at the traditional CMS Part B price in the below) and the manufacturer’s price at WAC (Figure 6).

Figure 6

Source: OhioHealth Riverside Methodist Hospital Chargemaster, CMS ASP Pricing Files, Elsevier Gold Standard Drug Database (GSDD), 46brooklyn Research

As can be seen above, there is an opportunity to get a cost below CMS’ Part B price with the Riverside Methodist Chargemaster (paying $13,635 instead of $16,078 for 480 mg of Opdivo; savings of 15%); however, the “opportunity cost” to get the potential savings to the CMS price point is to risk potentially getting charged $63K, or four times the Medicare price on the high end of the Riverside Chargemaster. Said differently, it doesn’t appear that the risk-to-benefit ratio of the pricing variability is proportional. There is more risk to incur a high drug cost for this medicine relative to the low cost based upon the potential maximum savings to the potential maximum upcharge. Saying it differently still, the manufacturer of this product has asked for around $15K for their drug, based upon their list price (WAC; or even ASP + 6%), and yet the healthcare system is potentially exposing us to prices as high as $60K. If you got a $40,000 bill for this product (as you would likely get at the discounted cash price), what was it about the manufacturer price that led you to pay well more than double the drug’s sticker price? (to say nothing of the cost you paid to have the drug infused…)

To be clear, the above should not be viewed as a criticism of Riverside specifically. Riverside’s chargemaster for this product does not appear all that different from other hospitals too (remember, we picked on Riverside merely due to their proximity to us). To demonstrate, we went and got another hospital chargemaster from another state (specifically the West Virginia University (WVU) Hospitals Chargemaster). In the figures below (Figures 7 & 8), we present the same information we did for Opdivo at Riverside Methodist, but replaced our data source with the WVU information.

Figure 7

Source: WVU Hospitals Chargemaster Files, 46brooklyn Research

Figure 8

Source: WVU Hospitals Chargemaster Files, CMS ASP Pricing Files, Elsevier Gold Standard Drug Database (GSDD), 46brooklyn Research

In interpreting the above, we note that both Riverside (Figure 3) or WVU (Figure 7) may potentially result in a billed amount of around $60K for this product. WVU has a lower range of expected cost experience on the infusion time (a roughly two-fold difference from min-to-max); however, their drug costs on this product are what really matter from an overall expenditure standpoint (not that we wouldn’t welcome paying $500 for an hour getting the infusion compared to $2,000). On the drug cost side, Riverside represents both the lowest possible price and the highest possible price. However, their lowest price is not their cash discount price, whereas the lowest possible price at WVU is the discounted cash price (which is a benefit to those without insurance, but not those with insurance as much). The regional variability above may suggest that there are advantages for payers to explore medical tourism within the United States (rather than abroad) for securing these very expensive drugs. If it is possible for an Aetna plan in central Ohio to pay Riverside $19k for Opdivo, certainly it may be worth it for Aetna to send a West Virginia-based member north to get that price (given Aetna plans as identified in WVU may incur a $26K cost for the same therapy) (Figure 9).

Figure 9

Source: WVU Hospitals Chargemaster Files, OhioHealth Riverside Methodist Hospital Chargemaster, 46brooklyn Research

Even if the plan has to pay for room and board of the member for a travel night, there just may be material savings for both the patient and payer to do this – despite it being the same drug administered at both facilities. Saying it again with the intent of increased sarcasm, what was it about the drug’s manufacturer price that led to this disparity in experience?

For you my friend, a special price

The final point we will make on this topic and drug for today is that it should not be lost on us that despite the billing working out to reach these numbers, it is not uncommon for medical bills – particularly in commercial insurance (i.e., employer sponsored health plans) – to have a contract provision that states that once all the charges are tallied up, reimbursement will be a certain percentage of the billed amount. We can see a little bit of that in the previous Figure 3 where the charges are listed as a percent rather than a dollar amount. However, look closely at the range of potential percentage-based charges. If you’re sometimes going to pay as little as 12% of the billed charges and other times as high as 65% of the billed charges, the end result is that payment will still be as wide of a range as we’ve observed (i.e., there is a five-fold difference from 12% to 65% much like there is a five-fold difference from $13K to $65K).

Yet, what is arguably more important than just the existence of disparate hospital Opdivo pricing (i.e., four-fold differences in min-to-max pricing), is that such a system of varied prices will inherently incentivize hospitals to bill as much as possible (i.e., 12% of $60K is more money than 12% of $13K).

Is more healthcare (as measured by more spending) always better (or even needed) healthcare?

While that philosophical question is perhaps a different matter, note that the math is such that there may be no difference in the net paid amount when we negotiate contracts as a percentage of billed amount. If a hospital can charge one plan 12% of $60K in billed costs (i.e., smallest percentage against highest observed cost), the net cost will be $7,200 (i.e., 0.12 x $60,000). Whereas if that same hospital charges a different plan 65% of the $13K billed amount (i.e., highest percentage against the lowest observed drug cost), the latter plan will actually spend more ($8,450; 0.65 x $13,000)!

As we have said repeatedly, when there are a dozen different prices for a drug, there is actually no such thing as the price for that drug. More to the point, in either scenario, the service offered doesn’t appear to have been any different. These chargemasters are, after all, for the same service (a drug via infusion), offered at the same hospital. Which means they can also reflect people (with different insurances) getting the same service, at the same provider, on the same day, at vastly different payment amounts. So the only difference seems to have been to raise healthcare costs for some and not others, without a clear link (at least in our minds) that would demonstrate that in raising that service cost, better healthcare was delivered to one insurance plan’s members over others. Conversely, if we accept that a hospital gives better healthcare to plans that it can charge more to, isn’t that whole new series of problems? (To be clear, we don’t think that is what is going on).

Just how functional can a market be if there are no actual prices which would appear to govern it? After all, if the goals of increased price transparency are that we can shop for these, how are people to respond to the same merchant setting many different prices for the same service, at the same time (i.e., different charges for different insurers)? Are we actually living in some sort of complicated barter system?

Well, to look into that, we decided to analyze the insurers’ costs within the Riverside Chargemaster to see how aggregate prices compare against the listed discounted cash price. This analysis sought to simply group the health plans together and compare how frequently the plan price was below, above, or equal to the discounted cash price for the listed product/service. While this analysis may fail to adequately treat those lines that have both listed costs and percentage based costs, it should be directionally accurate (from what we can tell, it is not common for an item to have both). As can be seen below (Figure 10; and for your downloading pleasure), the entities we’ve entrusted to barter our deals have various levels of success doing so.

Figure 10

Source: OhioHealth Riverside Methodist Hospital Chargemaster, 46brooklyn Research

To interpret Figure 10, we’re looking for big green bars (insurer secured a price from the hospital that was below the hospital’s listed cash price; all based upon one source – the hospital’s chargemasater file). However, we don’t see a lot of big green bars in Figure 10. And so, the above certainly makes us wonder, if these are the results for the prices we’ve legislated be “transparent,” what value is achieved through secret, negotiated drug pricing deals in the other “opaque” parts of the drug supply system? To be more specific, in looking at the above, only five insurers (plans on the x-axis) had any meaningful level of discounting of their prices (the collective experience of all listed hospital charges) against the hospital cash prices. The rest, which was overwhelmingly the majority of plans, had prices above the cash price (i.e., full blue bars for the percentage of service costs where their stated cost is higher than the cash price). Putting that into perspective, if we were the plan sponsors contracting with these insurers, we would wonder what benefits we received in securing their insurance prices (as opposed to just paying the cash prices to these facilities). To be clear, they’re liking getting some benefit – that ever-elusive percentage discount off of billed charges – but who does that really benefit?

As Charlie Munger once said, “show me the incentive and I’ll show you the outcome.” Are we REALLY surprised by rising healthcare costs when price is merely a fiction used to justify a a larger payout on a percentage-based reimbursement system?